Delegitimising China’s Naval Presence in the Indian Ocean Region

Summary: The growth of piracy off the coast of Somalia, since 2008, led to a proliferation of extra-regional naval forces in the region. China has sustained a three-ship anti-piracy task force in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) since last 14 years. These task forces have given an exceptional operational edge to the PLA Navy. With the impending removal of ‘Indian Ocean High Risk Area’ (HRA) due to decline in piracy, India along with other Indo-Pacific partners needs to delegitimise China’s naval presence and revitalise regional mechanisms like Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) to enhance maritime security in the IOR.

On 22 August 2022, in a development having far-reaching consequences for maritime security in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS)1 forwarded a submission to the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for removal of the ‘Indian Ocean High Risk Area’ (HRA) from 1 January 2023. The submission will be taken up at the next meeting of the IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) on 31 October 2022.2 Considering that the proposal has been backed by the Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO)3 , International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA), International Association of Dry Cargo Ship-owners (INTERCARGO),4 International Association of Independent Tanker Owners (INTERTANKO) and Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF)—cumulatively representing the bulk of the shipping stakeholders, the removal of HRA is a foregone conclusion.5

Background

Alarmed by the continuing increase in piracy and armed robbery in the waters off the coast of Somalia, the UN Security Council (UNSC) on 2 June 2008 authorised the patrolling of Somali waters for six months by the States having the capability to do so.6 Sanctioned under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, which provides for enforcement action, the counter-piracy efforts were to be undertaken in cooperation with the Transitional Federal Government of Somaliland the States were permitted to use “all necessary means” to stop “piracy and armed robbery at sea” including entering the Somali territorial waters. Since then, the UNSC has regularly extended the authorisations, with the last such extension adopted on 3 December 2021.7 Lately, the incidents of piracy within the HRA have declined to an all-time low and no incidents of piracy have been reported since beginning of 2021. Successful ship hijackings for ransom have also not been reported since March 2017.

The Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS), having participation from nearly 80 countries and several international organisations, is the principal international framework for coordinating anti-piracy activities in the Gulf of Aden (GoA). Other prominent organisations include the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Maritime Security Coordination Committee (MSCC), IMO, Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC), European Union Capacity Building Mission in Somalia (EUCAP Somalia), and the Shared Awareness and Deconfliction Initiative (SHADE).

HRA Extension and Subsequent Revisions

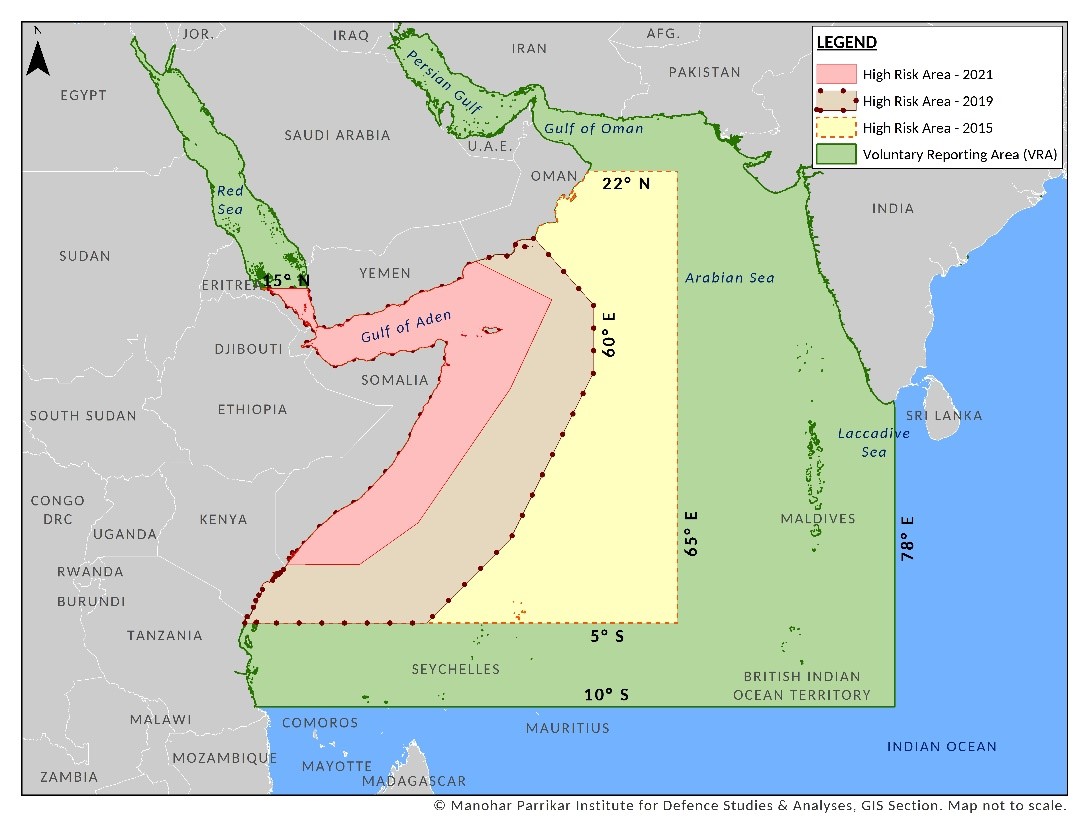

High Risk Area (HRA) is an industry designation for areas considered to be at higher risk of piracy.8 The United Kingdom Marine Trade Operations (UKMTO) operates a Voluntary Reporting Scheme (VRS) for the Indian Ocean, specifically Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Arabian Sea. In 2010, HRA was extended from 65° East longitude to 78° East longitude, after increase in piracy incidents off the coast of Somalia (see map below).9 The eastward limit of HRA was close to the western seaboard of India. This led to re-routing of east-bound merchant shipping close to the Indian coast, thereby impacting local fishermen. Indian fishing boats have also been fired upon, mistaken for pirate skiffs, as seen in the MV Enrica Lexie incident, of 15 February 2012. Further, hiring of private security, transit at ‘uneconomical’ speeds and payment of Additional War Risk Premium (AWRP), added to the cost of transportation. It has been estimated that the AWRP levied on almost 22,000 ships calling on Indian ports between 2000 and 2015, amounted to Rs 8,500 cores.10

Increasing piracy also spawned a new industry of Private Maritime Security Companies (PMSCs) and Privately Contracted Armed Security Personnel (PCASP) as also proliferation of floating armouries in the proximate waters of India. Estimates place their number at over 30, with each capable of storing up to 1,000 assault rifles, along with associated ammunition, adding to India’s maritime security challenges.11 The MV Seaman Guard Ohio incident (October 2013) is a case in point. The biggest terror strikes the country has witnessed, the 1993 Mumbai blasts and 26/11 incident, occurred through the sea route. At the peak of piracy, in 2011–12, PMSCs numbered approximately 180 and were reportedly worth US$ 6 billion, employing an estimated 4,000 PCASP.12 About 145–150 PMSCs were operating in the IOR.

Due to the economic and security implications, India sought HRA revision back to 65° East longitude.13 Indian naval forces undertook extensive counter-piracy operations, because of which no piracy attacks took place east of 65° East longitude for more than three years since 2012.14 In recognition of India’s persistent efforts and the trend of declining piracy, on 8 October 2015, the HRA was revised westward, shifting it over 1,400 kilometres away from the Indian seaboard (see map below). This resulted in substantial relief to the Indian shipping industry as well as addressed India’s maritime security concerns.15

Due to continuing reduction in incidents of piracy and on representation of the stakeholder organisations, the HRA was further shifted westward from India in 2019 (see map).16 Subsequently, in August 2021, the global shipping and oil industries again announced an agreement to reduce the boundaries of the HRA.17 The changes reduced the HRA boundaries to the Yemeni and Somali Territorial Seas and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) in its eastern and southern reaches (see map below). With the recent ICS submission, and its expected acceptance by the MSC of the IMO, the HRA would cease to exist from 1 January 2023.

Extra-Regional Presence in IOR: China’s Anti-Piracy Missions

A three-ship PLA Navy’s (PLAN) anti-piracy task forces (APTF) to fight piracy in the GoA was sent for the first time on 26 December 2008.18 Since then, China has deployed more than 120 warships, with claims of having escorted more than 7,000 Chinese and foreign ships over the period.19 Under the garb of assisting in humanitarian efforts, China also opened its first overseas military base at Djibouti in 2017.

After an APTF completes an escort mission in the GoA, generally lasting about three months, it usually undertakes port calls. These deployments, which have seen search and rescue (SAR), anti-terrorism, and humanitarian aid and disaster relief (HADR) exercises, would have led to a significant accrual in capability to conduct Military Operations Other Than War (MOOTW). The APTFs have also resulted in valuable military experience, in areas such as anti-submarine, air defence, anti-ship, and amphibious landing operations.20

In 2015, China also deployed a nuclear attack submarine (SSN) for anti-piracy operations in the GoA. SSNs, being stealth platforms, are ill-suited for anti-piracy operations, due to lack of ability to undertake surface operations. China’s SSN deployment therefore, clearly betrays a strategic intent. It is quite possible that the SSN deployment was meant to test the infrastructure and capability, including the necessary Command and Control and Communication protocols, for long range/long duration patrol by the SSNs and/or deterrent patrol missions by SSBNs (ballistic missile nuclear submarines).

SSN deployments for anti-piracy operations or otherwise, in the IOR, have not been reported since 2015 while conventional submarine deployments have not been reported since October 2018.21 This does not mean, though, that China has not deployed such assets since then. It is quite possible that the Chinese have developed the necessary infrastructure, expertise and the requisite command, control and communication protocols for prolonged and undetected SSN operations in the IOR.

The PLAN APTF anti-piracy operations in the GoA could be considered to be the largest and the longest sustained Out of Area (OoA) operations undertaken by any Navy post World War II. These operations have possibly given PLAN the capability of sustained limited power projection in the far seas. They have also resulted in a comprehensive and effective use of PLAN as instrument of the Chinese diplomacy and furtherance of their national interests, including utilising the opportunity presented to make further inroads in Africa, South Asia and the Mediterranean.

PLAN capability enhancement due to APTF operations is varied and multifaceted. Apart from getting a foothold in the IOR to ensure a permanent PLAN presence, they include enhanced decision-making ability of their Commanders in a long-distance operation scenario, engagement and interoperability with other friendly navies, communication procedures, crew morale, confidence in operating complex machinery and their maintenance for prolonged durations far away from their base ports, logistics supply chains and inter-ministerial coordination, to name a few.

Even as the PLAN has gained operational edge in GoA operations, it has become increasingly assertive in maritime affairs in the recent years. This is evident in its promulgation of the Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea (ECS) in 2013, the massive reclamation exercise undertaken in 2014–15 adding over 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea (SCS),22 its continued belligerence and coercion in the SCS and the ECS against Philippines, Vietnam and Japan and the recent and ongoing provocative manoeuvres against Taiwan. Despite the steady decline in the piracy incidents in the GoA over the years23 , and the steady downward revision of the HRA, the PLAN anti-piracy operations have not reduced, either in size or scope.

Apart from China, the threat of piracy has provided a reason to almost all extra-regional major powers to have a permanent naval presence in the region, encompassing ship deployment and naval bases.24 Apart from the Chinese base, Djibouti hosts Camp Lemonnier, home to the US Africa Command (AFRICOM) with around 4,000 personnel. Djibouti also hosts military facilities of several countries such as Japan, France, Germany, Italy and Spain.25 Saudi Arabia too has a presence.26

The naval forces in the anti-piracy operations in the GoA include the assets of EU under the European Union Naval Forces (EUNAVFOR) Operation ATALANTA, the counter piracy activities of the African Union, and independent anti-piracy patrols undertaken by individual countries, including Japan, South Korea, Iran and Russia, apart from India and China. US-led maritime initiatives include the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), a 34-nation multinational maritime partnership, operating out of Bahrain. Three Combined Task Forces (CTF) operate under the CMF, of which the CTF 151 is responsible for counter-piracy operations.27

India as Net Security Provider in IOR

The Indian Navy (IN) commenced anti-piracy patrols in the GoA from October 2008 and since then a ship has been deployed continuously. In 11 years, as on 2 June 2019, a total of 73 ships had been deployed which had escorted through the Internationally Recognised Transit Corridor (IRTC), a total of 3,440 ships, of which 3,027 were of foreign flag and 413 Indian flag.28

The Indian Ocean is central to India’s maritime interests and concerns. India’s location gives it a vantage point in the IOR and India’s size, trade links and its EEZ link its security environment directly with the extended neighbourhood.29 Several extra-regional nations look up to India as the first responder in a calamity, a net provider of security in the region, and seek collaborative partnerships in the maritime domain.

India’s intent to be prime security guarantor in the IOR is widely publicised and articulated. Most recently, on 9 August 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while chairing a UNSC session on Maritime Security, asserted that “India’s role in the Indian Ocean has been as a Net Security Provider”.30 The role of India as a NSP in IOR has also been actively supported by the US. The other primary Indo-Pacific partners and the members of the Quad such as Japan, Australia, France and the UK have also been largely supportive of India’s maritime security endeavours in the region.

The Indian Navy has been playing a maritime leadership role in the IOR, due to its multi-dimensional capabilities and active presence in the region. Ensuring maritime security and freedom of navigation in the Indian Ocean and the wider Indo-Pacific region is key security imperative and one of the key objectives of India’s engagement with its partners.31 IN is the only navy in the region that has a multi-dimensional capability, operates aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines, has the widest surveillance reach to monitor all the Indian Ocean chokepoints and has the widest range of bilateral and multilateral networks. As part of its foreign cooperation initiatives, the IN presently carries bilateral naval exercises with 14 navies and coordinated patrols with four, most of which are in the Indo-Pacific.

The IN has been actively working towards capacity-building and capability enhancement of navies of friendly countries in IOR by providing hardware and platforms, which includes ships and aircraft for the EEZ surveillance. India has also been expanding its outreach in the IOR by improving maritime domain awareness (MDA) and extending the operational reach of the IN through regular mission-based deployments (MDP). The re-orientation to MDP has meant that 15 warships of the Indian Navy are patrolling seven areas of the waters around India, beyond the country’s EEZ, keeping an eye on all entry and exit routes to and from the Indian Ocean.32 In addition to these deployments, Long Range Maritime Reconnaissance (LRMR) aircraft, like the Boeing Poseidon 8I planes, are tasked with flying sorties, almost every day, from INS Rajali in Arakonnam, Tamil Nadu and INS Hansa in Goa.

Apart from the significant capabilities of the Indian Navy, India has conceptualised and supported regional, multi-lateral maritime security organisations like the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS). The IORA has 23 Member States and 10 Dialogue Partners.33 The IONS has 24 members that permanently hold territory that abuts or lies within the Indian Ocean, along with 8 observer nations. The launch of the IORA in 1997 (earlier IOR-ARC), was the first effort to develop a region-wide multilateral structure.34

When India became the IORA Chair for 2011–13, it revitalised the organisation. Six Priority and two Focus Areas were identified to promote sustained growth and balanced development in the IOR.35 Maritime Safety and Security (MSS) is one of the two top priority areas of focus of IORA presently and there is an ‘IORA Working Group on MSS’ (WGMSS). The 2017 ‘Blueprint for Maritime Safety and Security in IORA’ serves as a base document for initiatives to be implemented by the Working Group.36

IONS, a voluntary initiative, seeks to provide an open and inclusive forum for discussion of regionally relevant maritime issues. Maritime Security is one of the four working groups of IONS. France is the current chair for the two-year term 2021–23. It is the author’s assessment that both IORA as well as IONS have not been utilised to their potential in respect of enhancing maritime security in the IOR.

Policy Implications

Delegitimise China’s anti-piracy forays

The removal of the HRA will come into effect on 1 January 2023, allowing charterers, ship-owners and operators time to adapt to the changed threat from piracy. Best Management Practices 5 (BMP5) will continue to provide the necessary guidance for shipping to mitigate the risks presented by remaining security threats in the region. Despite the removal of HRA, the Voluntary Reporting Area (VRA) administered by UKMTO has not changed. Ships entering the VRA have been encouraged to report to the UKMTO and register with the Maritime Security Centre for the Horn of Africa (MSCHOA) in accordance with industry BMP.37 It is unlikely that the extra-regional naval presence in the IOR is likely to reduce anytime soon, after the removal of the HRA. The US, EU, China and other countries’ anti-piracy patrol efforts in the GoA are likely to continue since presence in the area also accrues strategic benefits.

The rise of China’s maritime threat has been instrumental in the revival and growth of several bilateral, trilateral and multilateral naval joint exercises. Prominent ones include RIMPAC, Malabar and La Perouse and other trilateral exercises including US, Japan, France and Australia. The re-emergence of Quad 2.0 has been largely attributed to counter the maritime threat posed by China.

It is therefore in the collective interest of the larger Indo-Pacific maritime community to deny China the advantages it is gaining through the APTF operations and using it to extend maritime hegemony in the Indo-Pacific. This can only be achieved by delegitimising China’s anti-piracy operations in the GoA.

The legitimacy to the multinational anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia are provided by successive UNSC resolutions. With the imminent removal of the HRA and piracy off the coast of Somalia at an all-time low, there is a need for a re-think on the continuation of the UNSC resolutions authorising anti-piracy efforts in the IOR by extra-regional states.

India is currently serving as a non-permanent member of the UNSC, and will complete its term in December 2022. India, in partnership with the P5 and other non-permanent members of the UNSC, will need to actively work to seek discontinuation of the UNSC resolution authorising extra-regional presence for anti-piracy efforts in the GoA.

Strengthen IORA and IONS

At the same time, India, with support of the US and other likeminded nations of the Indo-Pacific, will need to strengthen the maritime security mechanism of the IOR. Regional maritime security mechanisms exist, both at the political as well as the execution level, in the form of IORA and the IONS, which, despite having the potential, have not been optimally utilised. Additionally, both IORA and IONS, have a wide regional representation in the form of dialogue partners and observers. Both IORA and IONS have Maritime Security as part of their charter and are best suited to undertake maritime security governance and execution roles in the IOR, if suitably strengthened and supported.

Further, these organisations have been conceptualised and supported by India, which has a vital stake in the maritime security in the IOR. IN is the most potent and capable navy in the region with the largest bilateral and multilateral networks. India’s role as a NSP, moreover, has been supported by the US and the wider Indo-Pacific Community.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. The ICS, a London-based global association of ship-owners and operators, representing over 80 per cent of the world merchant fleet.

- 2. “Shipping Industry to Remove the Indian Ocean High Risk Area”, International Chamber of Shipping, 22 August 2022.

- 3. BIMCO covers over 60 per cent of the global fleet and consists of local, global, small, and large and global shipping community of around 2,000 members in more than 130 countries.

- 4. INTERCARGO represents the interests of dry cargo ship-owners. It was convened for the first time in 1980 in London and has been participating with consultative status at the IMO since 1993.

- 5. For more on the HRA, See “Best Management Practices to Deter Piracy and Enhance Maritime Security in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea”, BIMCO, ICS, IGP&I Clubs, INTERTANKO and OCIMF, 5 June 2018.

- 6. “Resolution 1816 (2008)”, UN Security Council, 2 June 2008.

- 7. “Resolution 2608 (2021)”, UN Security Council, 3 December 2021.

- 8. “Indian Ocean”, United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations.

- 9. “Revision of the Piracy High Risk Area”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 9 October 2015.

- 10. “Ships Get Relief from Piracy Related Insurance Premium at Indian Ports”, The Hindu, 6 June 2016.

- 11. Ioannis Chapsos and Paul Holtom, “Floating Armouries in the Indian Ocean”, in Small Arms Survey 2015: Weapons and the World, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 216–41.

- 12. “The Security Association for the Maritime Industry (SAMI) Announces Voluntary Liquidation”, Maritime Cyprus, 19 April 2016.

- 13. “Revision of the Piracy High Risk Area”, no. 9.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. “Revision of Piracy High Risk Area”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, 9 October 2015.

- 16. “Subject: DGS Circular reg. Revision of High-Risk Area in Indian Ocean”, Indian Register of Shipping, 14 March 2019.

- 17. Jakob Paaske Larsen, “Change in Piracy Threats in Indian Ocean Prompts Re-Think of High Risk Area”, BIMCO, 17 August 2021.

- 18. Dr. Alison A. Kaufman, “China’s Participation in Anti-Piracy Operations off the Horn of Africa: Drivers and Implications” July 2009, https://www.cna.org/reports/2009/D0020834.A1.pdf

- 19. Guo Yuandan and Liu Xuanzun, “PLA Navy’s 14 years of Missions in Blue Waters Safeguard Intl Trade Routes, Win More Overseas Recognition”, Global Times, 1 August 2022.

- 20. Ibid

- 21. Manu Pubby, “Chinese Submarine Movements in Indian Ocean Down, Pakistan Navy Remains Choked In”, The Economic Times, 25 April 2019.

- 22. “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017”, US Department of Defense, 15 May 2017.

- 23. “Global Piracy and Armed Robbery Situation in 2021”, INTERCARGO, 21 January 2022.

- 24. “Race for Strategic Bases in Indian Ocean Region to Intensify: Gen Bipin Rawat”, Outlook, 11 December 2020.

- 25. Neil Melvin, “The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region”, SIPRI Background Paper, April 2019.

- 26. Eileen Whitehead, “Why Do So Many Countries have Military Bases in Djibouti?”, Peoples World, 31 August 2021.

- 27. Apart from CTF 151, CTF 150 deals with Maritime Security Operations outside the Arabian Gulf and CTF 152 relates to Maritime Security Operations inside the Arabian Gulf.

- 28. Dinakar Peri, “Indian Navy Steps up Anti-Piracy Patrol”, The Hindu, 2 June 2019.

- 29. Anurag Bisen, “India-United States Maritime Collaboration”, MP-IDSA Backgrounder, 8 April 2022.

- 30. “PM’s Remarks at the UNSC High-Level Open Debate on ‘Enhancing Maritime Security: A Case For International Cooperation’”, PMINDIA, 9 August 2021.

- 31. “Annual Report 2017–18”, Ministry of Defence, Government of India.

- 32. Sujan Dutta, “Indian Navy Informs Government about the Fleet’s Reoriented Mission Pattern”, The New Indian Express, 1 April 2018.

- 33. China, Egypt, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Russia, Türkiye, United Kingdom and United States of America.

- 34. Gurpreet S. Khurana, “Multilateral Structures in the Indian Ocean: Review and Way Ahead”, Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2018, pp. 11–23.

- 35. “Maritime Safety and Security”, Indian Ocean Rim Association.

- 36. Ibid.

- 37. “Shipping Industry to Remove the Indian Ocean High Risk Area”, no. 2.