Strategic Salience of the Gwadar Port: An Analytical Study

Gwadar Port has gained currency in the light of recent international developments that are increasingly focused on maritime-related economic activities. It has become an important reference point for people discussing the geopolitics and geo-economics of the South Asian region. The article explores in detail the strategic salience of Gwadar against the backdrop of the ongoing Baloch insurgency, the current activities being undertaken at Gwadar, the strategic outlook of Pakistan and China on the port and the implications it holds for China–Pakistan ties. Gwadar Port holds strategic significance due to its prime location and the massive investments by China to provide world-class facilities of docking at the port. The port has increased the existing economic and strategic interdependence between China and Pakistan.

INTRODUCTION

The twenty-first century has been characterised by several countries refocusing to invest ore and expand in the maritime domain. Presently, naval activities, especially among the eveloping nations, have assumed accelerated economic and political significance. In essence, ‘port’ in a country’s economy is the bridge between its land and sea economic activities. It occupies a crucial position and its utilisation influences the pace of progress of a nation. Some countries have even moved beyond their borders to capitalise on ports outside their own territory. This highlights the importance given to ports for controlling maritime trade routes and seafaring activities. Some of the busiest and most significant ports in the world include the Port of Shanghai in China, Busan in South Korea, Port of Singapore, Los Angeles Port, Port of Jebel Ali in Dubai, Port of Nagoya in Japan and Port Kelang of Malaysia.

In this context, recent international developments have witnessed the growing prominence of Gwadar Port and the consequential closer ties between Pakistan and China. Gwadar has emerged as an important maritime point in the Persian Gulf. A natural warm-water, deep-sea port, Gwadar resembles a ‘hammer-head’ and projects outwards from the south-western Arabian Sea coastline of Pakistan. Today, it is a site of advanced development in an otherwise poorly developed Gwadar district of the Balochistan province. Gwadar has become an important reference point in discussions on the geopolitics and geo-economics of the South Asian region. Therefore, it is imperative to study the present situation around Gwadar and assess the implications it holds for the future of China–Pakistan ties, regional security and maritime trade connectivity in the region.

The objectives of the study are to: evaluate the strategic salience of Gwadar Port against the backdrop of the ongoing Baloch insurgency; understand and assess the strategic outlooks of Pakistan and China on Gwadar Port; examine the current activities being undertaken at the port and the agencies involved in those activities; and analyse the anxieties of external countries over possible strategic and military use of the port by China in future.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF GWADAR PORT

The term Gwadar is a fusion of two Balochi words, guad meaning ‘wind’ and dar meaning ‘door’, thus understood as meaning, ‘The Door of Wind’.1 The political history of Gwadar Port is riddled with several conflicts between the rulers and local tribes. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the site of Gwadar simultaneously played different roles for different actors. As records show, it was:

at one and the same time, a dominion of the sultans of Oman, a source of income for the Gichki from Ketch, a strategic observation post for the British Government along the coast of Makran in the direction of Persia, and a staging-post of the Indo-European Telegraph Line.2

This multiplicity of interests resulted in the tumultuous events that make up the history of Gwadar.

Gwadar was first mentioned as a ‘potential maritime point’ in the 1954 survey of Pakistan’s coastline by the United States Geological Survey; it was then under the sovereignty of the Omani government.3 However, in 1958, the Gwadar enclave was officially bought by the Pakistani government from the then Government of Oman by paying about US$3 million.4 Since then, Gwadar has been in the possession of Pakistan and today, it is projected to become an important hub for trade, commerce and connectivity.

Pre-China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Developments

Pakistan recognised the strategic importance of Gwadar only in the 1990s and the work on the port began at the turn of the twenty-first century. The responsibility of port construction was awarded to the Chinese. In March 2002, the construction of the port began and the foundation stone was laid by the then Vice Premier of China, Wu Bangguo.5 The port was described as the ‘second great monument of China–Pakistan friendship after the Karakoram Highway’.6 It was in the year 2003 that the Pakistani government, for the first time in its budget, allotted Pakistani Rupees 16.7 billion exclusively for the construction of roads in order to link the ‘proposed new port of Gwadar’ with the rest of the country.7

The construction of the port was proposed to be completed in two phases. In October–November of 2004, the government revised the date of completion of the first phase from April 2005 to September 2005. The official reason cited was that although the existing draught depth of the port was naturally 12.5 metre (m), it had to be further dredged to 14m to accommodate larger ships.8 The estimated project cost of the first phase was Pakistani Rupees14.9billion, of which the Chinese funded US$ 217million and the Pakistani government contributed US$81 million.9

The second phase was planned to be constructed by the private sector at a cost of US$ 865million. To attract investments to the region, a special economic ‘tax-free’ zone was proposed to be set up in Gwadar on 10,000 acres of land; it would also allow for factories to be set up for the manufacture of export goods. To that extent, several concessions were offered to foreign investors for the second phase of development at Gwadar, which mainly included dredging and deepening of the port.10

Following near-completion, in February 2007, the Concession Holding Company, a subsidiary of the Singapore Port Authority (then known as the Port of Singapore Authority or PSA), won the contract to operate and manage the port.11The port was leased out for a period of 40years. Several controversies and speculations arose on the timeframe of the lease and on the intent of the port itself. Interestingly, the first ship that anchored at Gwadar in 2008came from Canada, carrying a shipment of about 52,000 tons of wheat. However, the PSA could not increase the revenue and found the operations not profitable. With the ongoing constructions in the second phase and owing to disagreements on the extent of landholdings to be given for the tax-free zone, the port came under the control of the China Overseas Ports Holding Company (COPHC) in 2013.12

GWADAR IN THE CONTEMPORARY CONTEXT

At present, the port is functional, albeit to a limited extent. Some of the proposed projects have been completed. It has been leased to the Chinese state-run company, COPHC, for a period of 40 years, with Pakistan holding 9 per cent share of revenue collection from gross revenue of terminal and marine operations.

The port was officially inaugurated on 13 November 2016 as part of the larger CPEC, with goods from Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang, journeying through the built corridor, reaching the port on 12 November. This was accompanied by the loading and unloading of Wellington cargo vessel at Gwadar. The event was important as it marked that ‘Gwadar had reached initial operational capability of container liner’.13 Following this, a consignment of 120 truckloads of goods was despatched on a Chinese ship to Africa,14 thereby pronouncing the first utilisation of the facilities at Gwadar. Since then, the port has assumed great strategic importance and relevance simply by virtue of its location, nature and advanced construction and facilities available at the port. Today, the port seeks to aid in managing the international traffic that is usually seen at the Strait of Hormuz. Table 1 provides an insight into the current infrastructure at Gwadar Port.

| Infrastructure | Details |

| Multipurpose Berths | 3 (each 200 m long) |

| RO-RO Facility | 1 |

| Service Berth | 1 (100 m) |

| 4.7 km long approach channel dredged to 14.4 m at outer channel, 13.8 m inner channel/turning basin and 14.5 m depth alongside berth | |

| Outer Channel | 206 m |

| Inner Channel Width | 155 m |

| Turning Basin | 595 diameter |

| Currently has the capacity to handle 50,000 DWT bulk carriers @ 12.5 m maximum depth | |

Source: Gwadar Port Authority, ‘Port Profile’, available at http://www.gwadarport.gov.pk/portprofile.aspx, accessed on 11 June 2019.

Note: RO-RO: roll-on/roll-off; DWT: deadweight tonnage.

Currently, a Pakistani naval base, PNS Akram, is located at the port. At Gwadar, the Pakistan Navy (PN) has established amenities for the local residents, including Naval Welfare and Medical Centre, educational institutions, Industrial Home Gwadar (a vocational centre of tailoring for the local women) and the Naval Utility Centre.15 The PN has been allotted a berthing space of 600m and is expected to provide for seaward security for the upcoming infrastructure at the port.

It is also imperative to make an observation about the present living conditions of the local people. There are about 20,000 fishermen who live in Gwadar, who are likely to be relocated owing to ongoing constructions. Reported interactions with the local people reveal that they are unhappy with the CPEC process due to several issues they are facing. Apart from the challenges of relocating to a new area, they are also victims of the land mafia that is taking illegal possession of their landholdings amidst the rising price value of the land.16 Moreover, unlike the other surrounding areas (like Sur Bandar), fishing at Gwadar can be done throughout the year and is not seasonal. Herein emerges the other major issue for the locals, which is losing their existing viable occupation of fishing. For these reasons, they are sceptical of the developments at Gwadar and are wary of the impending displacement that they would face. The first set of fishermen were displaced during the first phase of construction in Gwadar. Although many promises were made, they have not yet been provided with basic amenities, like ‘hospital, school and proper roads’.17

Is Gwadar Really Strategically Salient?

A perusal of the activities in the broader neighbourhood reveals that several new ports along the coasts of Gulf of Aden are coming up. The recent reports on the Duqm Port in Oman indicate this. Yet, considered solely from the perspective of both the countries who have invested in the port and their strategic outlooks, ceteris paribus, Gwadar is unequivocally being raised as a port of strategic consequence. Due to its natural depth and multi-infrastructure and facility provisions, Gwadar is going to be highly relevant strategically in the region.

STRATEGIC OUTLOOK OF PAKISTAN AND CHINA ON GWADAR PORT

Pakistan

It was President Musharraf who envisioned the development of Gwadar Port as a commercial centre. For him, it was a project that would facilitate and accelerate the prosperity of Pakistan.18 However, he realised that for the port to be a successful venture, it required the acceptance by local Baloch population and a proactive approach from Beijing.19

Strategic experts have observed that Pakistan’s attention towards Gwadar, which had otherwise been one of neglect for decades, was in some ways an outcome of its security dilemma with regard to growing Indian naval capability in the Indian Ocean during the 1990s, especially since 1992.20 This became all the more imperative with the launching of Operation Talwar and another major naval exercise, Summerex, by the Indian Navy during the Kargil conflict. The exercises were aimed at blocking Karachi Port of Pakistan, where a naval base is also situated, with the goal to choke Pakistan’s trade channels. These events forced Pakistan to consider an alternative and Gwadar seemed a viable option. With a natural draft of 12.5m, and dredging work proposed to deepen it further to 20m, it is being designed to handle huge tanker ships and have a feasible environment for restationing its naval bases.

Until Gwadar came to be developed, Pakistan had two major ‘operating international deep-sea ports’, namely, Karachi Port and Port Qasim. As per officials, as Karachi Port is located within a highly populated city, bursting at the seams, it experiences ‘significant physical limitations’ and the slow pace of its growth cannot match the needs of the growing demands of the country.21 With regard to Port Qasim, as per official documents, the major limitation of the port is its location, which is about ‘40km from the open sea’. Thus, although it has scope for expansion, it has certain cost disadvantages and its ‘speed for development is hampered by its up-stream location’.22 Positioning itself in this framework, Pakistan finds it only rational to invest and develop the Gwadar Port, which offers far greater benefits than disadvantages from a maritime connectivity point for Pakistan.

China

China’s strategic imperatives for capitalising on construction at Gwadar seem to have geo-economic (closer to western China and shortens its distance to West Asia and Africa), geopolitical (closer ties with Pakistan and link between Central, West and South Asia) and geo-strategic (control over the port) dimensions. Gwadar is the jewel in the crown of China’s CPEC initiative in Pakistan.

From a geo-economic aspect, capitalising on Gwadar offers a strategic solution that, to some extent, resolves China’s ‘Malaccan dilemma’ as it provides an alternate trade route. It also reduces drastically the time and distance for China’s goods to reach Africa and West Asia. The distance would be just 2,500 miles, which is significantly less than the current 9,500 miles route; and the time taken would be reduced to 3–4 days instead of the current duration of two weeks.23 When time–distance requirement for the transport of goods between countries reduces, it also simultaneously opens up option of expanding the scope for goods traded to include perishable ones that were otherwise not being considered due to excess consumption of time. Thus, essentially, it broadens the scope of trade between the countries. Moreover, the route through Gwadar significantly reduces the cost per container, which will make it highly economical and cost-effective.24 An operational and active trade corridor linking western China would also help it develop its backward Xinjiang province into a transit hub.

On the geopolitical front, China’s deepening tryst with Gwadar is inevitably strengthening its all-weather bond with Pakistan. As many analysts have observed, it must be noted that ‘China’s presence in Gwadar is occurring in the context of Beijing’s increased economic and political presence in the Middle East, where its interests do not always converge with those of Europe.’25 China’s presence in Gwadar could also, in effect, provide mileage to its mediatory role in the Pak-Afghan relationship and the reconciliation process in Afghanistan.

China’s control over Gwadar Port has an important geo-strategic dimension as well. Several factors indicate that Gwadar could be converted into a ‘naval harbour’.26 Besides this, its location—just about 120 miles from the Strait of Hormuz, which sees over 30 per cent of the global oil flows—places China at an advantageous position in the Northern Indian Ocean. China’s existing base at Djibouti is limited in scope and therefore, its presence in Gwadar greatly enhances its stakes in the region and offers multiple options for maintaining high-quality surveillance over traffic movement and activities in the Indian Ocean Region.27 From a military standpoint, Gwadar Port also offers a strategic location to set up listening posts in order to monitor naval and maritime activity in the Gulf region.28

A Pakistani naval official had confirmed in November 2016 that ‘ships of the Chinese navy will deploy alongside the Pakistani Navy for the security of the Gwadar Port’.29 This is perhaps obvious because building of any infrastructure requires a proportionate system of security to safeguard it. Statistics show that Pakistan would be unable to absorb the capital inflow and is heading towards a major debt crisis. In such a scenario, China would naturally claim ‘strategic equity’ on the port and ‘reinforce its grip over crucial assets in Pakistan’.30

Through Gwadar, China is probably sealing for itself a firm position to overlook the sea traffic in Western Indian Ocean. Labelling the umbrella initiative of CPEC as enabling world connectivity and prosperity, it is building for itself a neo-colonial state in Pakistan. Despite criticism from domestic economic scholars and concerns of the Parliament, under the tag of being iron brothers, Pakistan at present is blind to, and perhaps overlooking, the larger implications of its growing economic dependence on China.31Under its bilateral debt to China, Pakistan has to pay US$615 million between May 2020 and June 2021.32

ONGOING EFFORTS TO ENHANCE THE STRATEGIC SALIENCE OF THE PORT

At present, the provision of highly advanced facilities at Gwadar could make it extremely relevant in the Gulf of Aden. Besides being a natural deep-sea port, it has its own locational advantage. To that extent, the strategic salience of the Gwadar is likely to evolve further as China and Pakistan are expected to bring in more resources and energy into their efforts to raise Gwadar as a port of consequence.

Agencies Working in Gwadar

The port is owned by the Gwadar Port Authority, an independent organisation that functions under the Ministry of Ports and Shipping, Government of Pakistan. It came into effect through the issuance of an ordinance on 17 October 2002. Its major function is to overlook the entire development of infrastructure at the port pertaining to ‘construction, operations, management and maintenance’, and regulate the different private entities working in the site.33

Another statutory body of the Government of Pakistan, the Gwadar Development Authority (GDA), is also engaged in the activities at Gwadar. The body was set up in October 2003 to specifically implement the ‘Gwadar Master Plan’ that was introduced in 2002.34 The Master Plan had initially focused solely on the ‘land use’ of Gwadar. Now, it includes the ‘Internal Road Network, Land Zoning and vision for future Gwadar’.35 It is interesting to note that the Chairman of the GDA governing body is the Chief Minister of the Balochistan province. The GDA currently has over 347 staff employed in various activities and projects.

The port itself is operated by China Overseas Ports Holding Company Pakistan Pvt. Ltd (COPHC Pakistan), a branch company of COPHC based in Hong Kong. As per the concession agreement, the COPHC took command over the port and the free zone of Gwadar on 16 May 2013 for a period of 40years. It has ‘diversified interests in the field of Maritime & Logistics’ and the major objective it pronounces for Gwadar is its development as a ‘hub of maritime trade in the whole region’.36 The COPHC has three of its subsidiary branches working in Gwadar.

The Gwadar International Terminals Limited is focused on capitalising on the various opportunities that Gwadar presents, and accordingly developing the facilities that would be needed by the clients who dock at the region. This unit of the COPHC is engaged in building strategic partnerships through ‘mutual trust’. Apart from providing cargo handling equipment and storage, their general services include: ‘Customs Clearance Facilities, Specialized/Tailor-made stevedoring services (on request), Bunker & Fresh Water Supplies (on request), Ship Chandler Services (on request) and other information regarding Shipping Agents, Transportation, etc.’37 They have also set up a ‘desalination plant’ which can supply up to 100,000 gallons/day of drinking water to ships calling at the port.38

Gwadar Marine Services Limited deals majorly with ‘berthing’ and related operations. It includes a variety of other services, like ‘Pilotage, Tugging, Navigation, Berthing/Unberthing and Handling of all types of Cargo Vessel, etc.’39 It also comprises of other facilities, like ship chandler services, fresh water supply, medical services, bunker supply and crew arrangements.

Gwadar Free Zone Company Limited is yet another branch of the COPHC and is involved in building a customised platform of free zone area in the Northern Harbour of the port for global connectivity. It covers over 923 hectares and has permanent exemptions of tax and duties. It is aimed at ensuring the port can also be a viable alternative for industries that are transport dependent. Thus, it enables an optimisation of transport flows within the port. Besides these, the free zone businesses also include bonded warehousing, packaging/labelling, trans-shipment, imports and exports, value added exports, international purchasing, transit, distribution and other related businesses.

Activities being Undertaken at Gwadar

As per the official CPEC website, there are currently about 12 proposed projects and constructions for Gwadar, including the Gwadar East Bay Expressway, which is one of the main links to connect to the network of national highways. Estimated to cost around US$168 million, it was proposed to be completed by October 2020; the latest position, however, is unavailable.40 It is being supervised by the Ministry of Maritime Affairs, Government of Pakistan.

With the aim of easing accessibility and providing faster means of transportation, a New Gwadar International Airport is also currently being constructed at Gurandani (located about 28 kilometre [km] east of the city of Gwadar). The estimated cost of this project is US$230million, all of which is being financed by a grant by the Chinese government.41The airport would have both domestic as well as international flights. Other projects include the ‘Construction of Breakwaters’ and ‘Dredging of Berthing Areas and Channels’, aimed at ensuring smooth shipment at the port, and also for facilitating the construction of additional terminals. For the first one, the cost is US$123 million, which is a combination of the Chinese concessional loan and grant, while the other costs about US$27 million, which is being provided as concessional loan by the Chinese government.42

The US$32 million project, titled ‘Development of Free Zone’, is aimed at providing a backup port for the operations at Gwadar. It still requires addition of basic infrastructure facilities, like road connectivity, power supply and others. It is being supervised by the Ministry of Ports and Shipping and the Ministry of Commerce, Government of Pakistan. There is a project, ‘Necessary Facilities of Fresh Water Treatment, Water Supply and Distribution’, that is focused on catering to future water demands and waste disposal requirements of the port as well as the city itself. This particular project is being implemented by the GDA and supervised by the Planning and Development Department of the Government of Balochistan.43

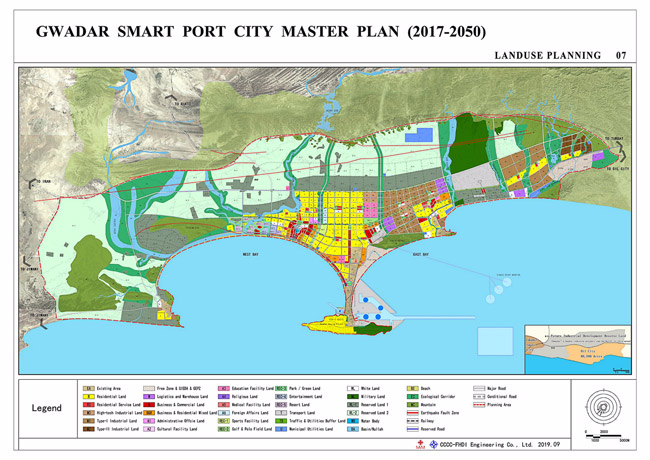

Other major flagship project is the Pakistan China Friendship Hospital. It aims at the upgradation of the existing 50 bedded hospital at Gwadar to six blocks, with residential provisions, laboratories, medical infrastructure and equipment. With a vision of creating state-of-the-art medical facility, the project is spread over 68 acres of land.44 Pak-China Technical and Vocational Institute in Gwadar and Gwadar Smart Port City Master Plan are initiatives that have been approved and are aimed at achieving a holistic vision for Gwadar’s development. It must be noted that, of the 12 proposed projects, some of them are yet to be discussed and approved.45 These include the Bao Steel Park, petrochemicals, stainless steel and other industries in Gwadar, development of Gwadar University (social sector development) and Gwadar Livelihood Project. Figure 1 provides a pictorial representation of the proposed plan and infrastructure projects for Gwadar.

Figure 1 Proposed Plan and Infrastructure Projects for Gwadar

Source: GDA, Pakistan, available at http://www.gda.gov.pk/masterplan/, accessed on 08 March 2021.

Data on Freight Movement through Gwadar

Initially, in 2008, the port was only handling government imports of wheat, which eventually extended to include fertilisers as well.46 However, after handing over to COPHC in 2013, the port has been handling equipment mostly pertaining to its own infrastructure development. The managing of other goods has been limited. It must be noted that extensive data relating to the same is not accessible. Table 2 shows the traffic forecast made by the Government of Pakistan in its Eleventh Five Year Plan (2013–18), also entitled ‘Pakistan 2025: One Nation–One Vision’.

| Sub-sector | Units | 2012–13 | Targets | |||||

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | ||||

| 1. | General and Containerised Cargo | Million tons | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.08 |

| 2. | Liquid Cargo | Million tons | 0.05 | 0.053 | 0.056 | 0.060 | 0.064 | 0.068 |

| 3. | Dry Bulk Cargo | Million tons | 1.97 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.50 | 2.71 | 2.93 |

| Total Cargo | Million tons | 2.79 | 2.99 | 3.22 | 3.54 | 3.80 | 4.08 | |

| 4. | Containers (TEUs) | Nos. (000) | 100 | 105 | 110.25 | 152.09 | 174.90 | 201.14 |

| The containers (TEUs) handling of the Gwadar Port is expected to increase within two years owing to the operations of the Port taken over by the state-run Chinese firm COPHC. | ||||||||

Source: Government of Pakistan, ‘Transport and Logistics’, in Pakistan Eleventh Five Year Plan (2013-2018), Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform, Islamabad, available at https://www.pc.gov.pk/uploads/plans/Ch27-Transport-logistics2.pdf, access ed on 2 July 2019.

Note: TEUs: twenty-foot equivalent units.

The data available in the official government document, ‘Pakistan 2025: One Nation–One Vision’, brings to light several observations. Primarily, it highlights the importance and centrality that Islamabad accords to the CPEC project, and specifically to the Gwadar Port. The mention of the influence of the COPHC, which is perceived as helping to increase the traffic at Gwadar, is also notable to understand the positive expectations that the host government holds.

STRATEGIC SALIENCE OF THE PORT

As a commercial port, Gwadar is very attractive for docking of ships. This is supplemented by several factors, like its provision of about 70,000 deadweight tonnage (DWT), draught of 14.5m which allows for convenience in heavy cargo shipment and direct docking at the port and extensive berthing facilities.47 The upcoming free zone is an added incentive. However, the projects are yet to be completed and the funds released so far do not meet the estimated requirements.

On the military front, Pakistan, as part of ‘normal military cooperation’, has received two surveillance ships from China for security purposes in the region.48 Reports indicate that Pakistan is awaiting the delivery of four advanced warships, the ‘Type 054A/Jiangkai II-class frigates’ which are Chinese built, to aid its security capability at the port.49 Both the countries have already performed a few naval exercises at the port; and for most of these, media coverage has not been allowed. As of now, the naval activities are limited, but clearly, they would eventually increase as the projects near completion and the port sees more activity. Majority of these activities would be for providing security to the port infrastructure and operation.

It must be noted that China has also heavily invested in mining activities in Balochistan, particularly so in the Saindak mine. Until the proposed railway lines and oil–gas pipelines are completed, the resources extracted from the mine can be shipped to China via Gwadar. Clearly, this is another reason for Gwadar being the fulcrum of Chinese investments in Pakistan. However, further investment feasibility remains to be seen considering the inhospitable environment in the province due to insurgency-related incidences and violence, as well as the geographic terrain and weather conditions, which can act as possible deterrents for customers, raising concern about safety of the goods. In order to protect against both conventional and non-conventional threats, the PN has raised Task Force-88 (TF-88) to address the issue of security of Gwadar Port.50

INSURGENCY AT BALOCHISTAN AND THE GWADAR PROJECT

Often, it has been noted that the location of Gwadar in insurgency-inflicted Balochistan province has been a disadvantage. The constructions at Gwadar face an immense challenge from the insurgents in Balochistan. The Baloch nationalists have been continually opposing the port for two primary reasons: one, Chinese capitalisation of the Gwadar Port; and two, the rapid surge in non-Baloch population in the area, which might reduce the Baloch to a minority in their own state. The unrest in the region has had several repercussions on the activities at Gwadar, such as attacks on, and killing of, several Chinese personnel and destruction of some completed projects. In response, the Chinese personnel have been provided security and the Pakistani government and media have issued statements claiming to have captured many attackers. The Pakistan government has set up a special unit in the army to this effect, known as ‘ Special Security Division’ (SSD), consisting of 9,000 Pakistan Army soldiers and 6,000 paramilitary forces personnel.51 This portrays the efforts of the Pakistani government to maintain a stable and strong relationship with China. The swiftness in Islamabad’s response highlights the tremendous premium it places on the bilateral ties with China and on the success of the project itself.52

Meanwhile, some scholars perceive the location of Gwadar in Balochistan as an asset. The particular factor of access to the sea is the greatest asset of Balochistan when viewed with regard to the landlocked countries of Afghanistan and Central Asia’s five ‘stans’.53 When the port at Gwadar becomes completely operational, the province would witness ‘hectic activity as a result of the passage of an unending line of trucks, trailers, buses and other forms of transport on newly built connecting highways’.54 There is a proposed plan ‘for constructing a railway between Quetta and Gwadar or between Chaghi and Gwadar’.55 This highlights the economic development opportunities Gwadar holds for Balochistan. It may also support the government in dealing with the insurgency issues in the area.

The Balochistan Liberation Army, which engages in the open opposition of the constructions at the port, is the voice of the local Baloch nationals. Apart from the above-mentioned reasons, the locals have reservations about the port’s development as most of the projects have been leased and contracted to ‘non-Baluchi foreigners from the provinces of Karachi and Punjab’.56 Moreover, the lands in the area have been purchased by property developers and others from outside of Balochistan. All of these add on to the existing sentiment of resentment that the Balochs hold towards them (Punjabis and residents of Karachi) due to their domination in nearly all fields in Pakistan. It further deepens their feelings of being a minority, neglected and alienated. They express their grievance by resorting to violence, in particular on the personnel working on the project, and damaging any progress made on the constructions.

COMPARING GWADAR VIS-À-VIS CHABAHAR PORT

Located at a distance of about 72km from each other, the Gwadar Port in Pakistan and Chabahar Port in Iran have been addressed as ‘strategic geopolitical launch pads’ for China and India respectively.57 The similarity is the immense economic significance these ports hold for the host countries (Pakistan and Iran), as well as for the countries investing in container building and other shipment constructions at the ports (China and India). However, one major difference to be noted between the two ports is the intensity of insurgencies present in the region they are located in.

At another level, the nature of investment aid by India and China has varied nuances that percolate and impact the depth of economic dependence between them and the host countries. Also, while Gwadar has seen a surge in building of settlements to accommodate the Chinese population working in the port, there are no such external demographic infusions at Chabahar from India. Another dimension is the stance and preference of Afghanistan, which is the land bridge for these countries to reach Central Asia. Afghanistan sees developments at Chabahar as a welcome and win-win gesture as it perceives it as an alternative to its dependence on the ports at Pakistan for its maritime connectivity.58

ANALYSIS AND SOME OBSERVATIONS

Projects, Funds at Gwadar and the China Factor

Let us consider whether the projects that have been proposed for Gwadar are indeed necessary and if so, whose needs are they serving. As much as these projects have their own purpose and credibility, a perusal of the plans brings to the forefront a speculation: is Gwadar Pakistan’s vision or a Chinese ambition? The constructions at Gwadar are indicative of the Chinese model of ‘creating supply to create demand’.59

Of course, the steady execution of individual projects around Gwadar Port is providing further mileage to the strategic salience of Gwadar. However, it cannot be ignored that it has more benefits for China than Pakistan at the end of the day. The reduction in duration for transportation of goods implies that China can now include more goods in its trade, such as perishable and low-shelf-life goods, which otherwise were not being traded due to the time taken to deliver them. Also, China has diversified the actors it has involved in the constructions at the port. Creating multiple agencies under the broad umbrella of COPHC, it has seeped and intervened in a multi-fold and multi-pronged manner. In the long run, China would be so deeply knit in the working of Gwadar that it could be difficult for it to be replaced by Pakistan after the contract period of 40 years expires.

The funds to all the projects are primarily being provided by China either as grants or concessional loans. It is clear that Pakistan is perhaps knowingly blinding itself and walking into the natural course of debt trap that lies ahead of it. The investments are extremely large for the Pakistan economy to be able to afford timely repayment and avoid the impending crisis.

Local Lives and Facilities

The lives of the locals are being ignored. Although a desalination plant has been constructed, the local people are still facing the issue of water shortage. Indeed, after being displaced and relocated, most of the promised amenities have not been provided and the localities are devoid of access to basic facilities. This is adding on to the resentment of the Balochis who are continually opposing the construction. All these issues complicate the insurgency situation that could take on different manifestations and pose a deeper threat to the stability in the region.

Sustainability

Gwadar is naturally endowed with benefits of being a deep-sea, warm-water port. As much as these artificial constructions elevate its relevance and potential, the sustainability factor is significant to consider. Another dimension of the same is: would these artificial set-ups add strain and slowly erode away the feasibility of using the port in the longer run? These speculations gain prominence amidst growing debates on environmental degradation and global warming.

Implications for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Gwadar is one of the most important projects under the larger CPEC initiative, which in turn is regarded as a flagship project under the BRI. China has sought to raise CPEC as a model for displaying its capacity-building potential and financial strength. In fact, so far, the developments have been portrayed as progressing positively well. Thus, China’s ambitious developmental plans and constructions at Gwadar can be seen as a marketing strategy for it to display its BRI as a ‘win-win’ for other countries.

Is the Naval Base Viable for China?

Some scholars are of the opinion that China’s interest in using the port as a naval base could be limited as it would not be able to deploy its modern destroyers and vessels at Gwadar.60 However, there is a counter-argument that with China investing heavily in vessel building and enhancing its naval power across oceans, it may still have the wherewithal to make its naval presence felt in Gwadar without subjecting its eastern coast to any major vulnerability. The proximity of the port to the Strait of Hormuz and growing Chinese investment in Gwadar to develop it as a successful commercial venture would demand that China remains mindful of the security aspect of its engagement in a place as strategic as the Gwadar Port.

New Routes to Reach Central Asia via Gwadar?

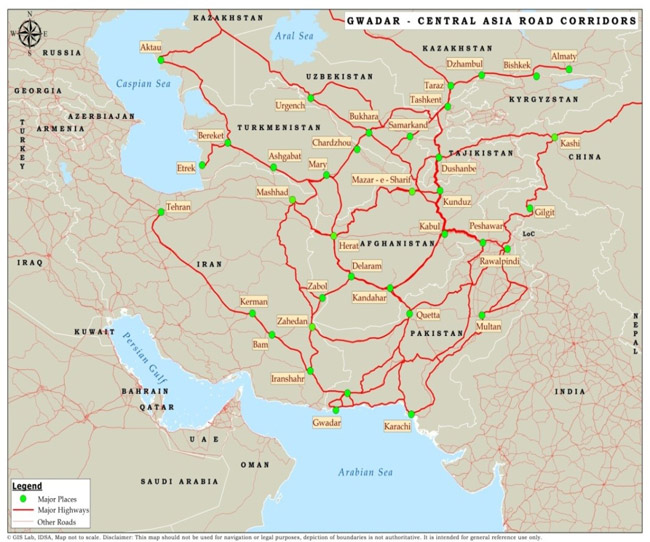

Perhaps, for China as well as Central Asia countries, there is a possibility of exploring a new route to reach Central Asia via Gwadar. Figure 2 depicts the corridors connecting Gwadar with Central Asia. The route could begin from Gwadar, move towards Quetta and enter Afghanistan passing through Chaman, and eventually connect to Kandahar and reach Central Asia via Pamir Highway.61 This would enhance and expand the connectivity of Gwadar. However, this is contingent on several geopolitical factors, including viability of the transit route, the interest of countries to explore the new route, response of Afghanistan to the route and so on.

Figure 2 Corridors Connecting Gwadar with Central Asia

Source: Corridors were mapped out by Dr. Vivek Dhankar, G.I.S. Technical Officer, MP-IDSA. The author is thankful to him for the same.

ANXIETIES IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD AND BEYOND

Gwadar has raised concerns in the neighbouring South Asian countries, especially India, as also countries in the West, because of its potential for enhancing China’s strategic capacity in the western Indian Ocean Region.

Gwadar has assumed an important dimension in the Sino-Pakistan bilateral ties. With leaders in both countries calling each other ‘all-weather friends’, joint activities and investments at Gwadar as part of the CPEC have brought the two countries closer. Both countries have their own strategic perceptions on Gwadar. For Pakistan, it aids in developing the economy of the region, while for China, it is an important transit route which allows it to reach the coasts of Africa in less than four days and reach Dubai in one day as compared to prior two weeks in both cases; it also helps China to develop and connect its western region to the nearest seaport.

The major anxiety of the countries in the region is that the port could be converted into a military strategic hold, where China could form its naval base. There have already have been some developments that point to this. Moreover, in preparation for any possible rise of competition in the region, China is deliberately pursuing a policy of ‘strategic vagueness, thereby gaining the opportunity to escalate naval activity, at a time of their choosing’.62 An added element is the ‘lack of an articulated Chinese maritime policy for the Indian Ocean, which further accentuates the uncertainty of intent’.63 In effect, such actions result in the growing security dilemma of the neighbourhood countries. It also complicates the delicate existing regional security complex.

In India, China’s proactive engagements in the region have always been a cause of concern. The general perception has been that the large-scale constructions in Gwadar are being countered by India through its involvement in the constructions at Chabahar Port in Iran. However, official government statements have stated clearly that there is no comparison between the two.64 Chabahar is solely a commercial enterprise, while Gwadar is a military strategic enterprise. In Iran too, there exists concern about the nature of development in Gwadar, which is viewed as a competition to Chabahar.65 As a goodwill gesture, the Iranian government had proposed building a link between Gwadar and Chabahar in order to facilitate cooperation over competition. However, this has not materialised.

The extent of China’s involvement in Gwadar has also raised concerns in the United States (US) regarding China’s strategic ambitions in the West Asian region.66 WikiLeaks data reveal that although the US has not made significant statements to this effect in public, it is closely following the developments at Gwadar. However, the US anxiety about Chinese presence in Western Indian Ocean in general, and Gwadar in particular, has been palpably of a lower order than its concerns about Chinese activities in the Pacific.67

CONCLUSION

The Gwadar Port of Pakistan, being extensively developed by China, has gained currency in light of recent international developments that are increasingly focused on maritime-related economic activities. Control over port activities and regulation of sea lines of communication provide advantages of security as well as economic trade benefit.

>Gwadar is a natural deep-sea port located in the warm waters of the Arabian Sea on the western coastline of Pakistan. Owned by Gwadar Port Authority of Pakistan government, it is operated by a Chinese state firm, COPHC. The port holds immense strategic significance due to its prime location as a potential maritime choke point in the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz through which the majority of world’s oil trade passes. Though the construction began in the beginning of the twenty-first century, it was only in 2015 that the port got subsumed under the larger CPEC. Since then, its importance and centrality to the bilateral ties of China and Pakistan has only increased.

Pakistan perceives Gwadar as a solution to its underdeveloped insurgency-inflicted Balochistan province. The functional port of Gwadar would lift burden off the Karachi Port, and also increase Pakistan’s relevance in the Indian Ocean Region. Thus, besides facilitating its economic growth and improving the situation in the province, the port could also increase Pakistan’s stature in the international arena. Meanwhile, for China, Gwadar is purely a strategic venture. It not only helps resolve China’s Malaccan dilemma but also significantly reduces the transportation time and distance for its trade with Africa and West Asia, whilst developing its western region. Along with this, the port can also be used by China for supplementing its military base presence in Djibouti. Furthermore, the nature of China’s engagement in Gwadar strengthens its model of creating economic interdependence so deeply that it cannot be neglected by the host country.

The agencies involved in the port include Pakistan government-owned Gwadar Port Authority and GDA; and the COPHC, which has three of its subsidiary branches working on different projects in Gwadar. The COPHC is currently the primary authority controlling the activities in Gwadar. Projects being undertaken at Gwadar include water treatment plants, express highways for connectivity, berthing facilities, cargo equipment services, skill development of the local inhabitants and others.

A major challenge to the constructions at the port is the opposition by local Baloch population. They have lost their landholdings to outsiders and are also losing their primary employment of fishing due to the constructions. Their grievances are being ignored by the government. As a result, their dissatisfaction and resentment towards Chinese workers is being expressed through violence on the workers and by damaging the infrastructure being constructed. At present, the freight movement is limited at Gwadar, but the nuisance potential of the Baloch insurgency is likely to grow once the freight movement increases over time. Therefore, the government needs to exhib