Manipur Blockade: A Tale of Vested Political Interests and Exclusivist Narratives

In a liberal democracy like India, pluralism should ideally inform everyday life. Sadly, this is not always the case on the ground. The latest blockade of the National Highway 39 (NH-39) connecting Imphal (Manipur) with Kohima (Nagaland) by the Naga Students’ Federation (NSF) and the All Naga Students’ Association Manipur (ANSAM) since April 12, 2010 is one such example of an exclusivist and intolerant attitude, unacceptable in a democracy like India that celebrates ‘unity in diversity’. It not only goes against the very idea of ‘humanitarianism’ but is also based on deep seated ‘meaningless’ ethnic hatreds of the other. Worst of all, when the rest of India and the world are marching ahead in an interactive and inclusive way despite numerous odds, the people of Manipur and Nagaland are marching backward: towards nostalgia, territorial exclusivity, xenophobia and ‘ghetto like’ tendencies which are out of sync with the modern world.

[Click to enlarge]

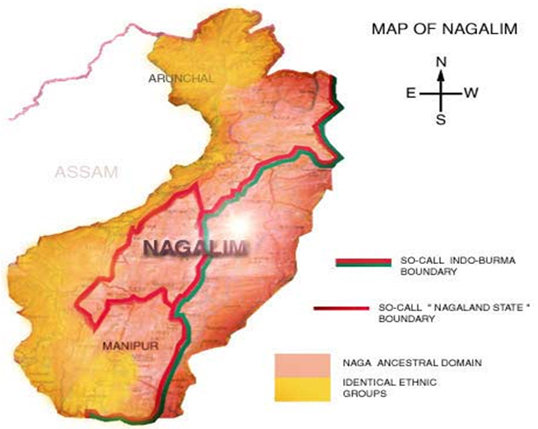

Why has this crisis suddenly come about between Manipur and Nagaland and that too, at this particular juncture? Meiteis and Nagas have been at odds, violently so at times, due to the demand by the Nagas, specifically by armed outfits like the National Socialist Council of Nagalim led by Thuingaleng Muivah and Isaac Chisi Swu [NSCN (IM)] that the four hill districts of Manipur, namely, Chandel, Tamenglong, Senapati and Ukhrul, be included as part of their “Greater Nagalim” (See Map below). Meiteis are wary of this territorial demand as it would result in the loss of 90 per cent of their territory and they being left with just 10 per cent territory comprising of the Imphal valley. Moreover, non-Naga tribes like the Kukis and the Thadous (the largest hill tribe in Manipur) inhabit the hill districts along with the Naga tribes and are against the unification agenda of the NSCN (IM).

Source: www.nscnonline.org

Given these differences between Meiteis and Nagas, the present blockade of the NH -39 has come about because of three reasons:-

First, the blockade was started on April 12, 2010 by ANSAM protesting against the holding of elections to six Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) in the hill districts of Manipur. Over 200,000 voters were exercising their ‘right to vote’ to elect 39 representatives to the ADCs of Chandel, Churachandpur, Ukhrul, Tamenglong, and Senapati districts. These elections were being held after a gap of 20 years. The first phase of the elections was held on May 26, 2010 in Chandel, Churachandpur and Sadar Hills in Manipur. The second phase was held on June 2, 2010 in Ukhrul, Tamenglong and Senapati districts. And this is where the sub-text of inter-ethnic politics is playing out its destructive role. From an inter-ethnic perspective (read Naga versus Meitei), holding of elections to the ADCs especially in Ukhrul, Tamenglong, Senapati and Chandel districts have two significant political implications.

- The participation of the people in the hill districts, especially in Chandel, Ukhrul, Tamenglong and Senapati districts in these elections is a “thumbs down” to the Naga territorial unification agenda as it gives representation to Nagas within Manipur in democratic institutions, in which they will have their due say. It also creates an added fear for armed groups like the NSCN (IM) that the ADC elections could prop up alternative Naga leaders, who may see positive political stakes in being a part of Manipur and thus enjoying enough political autonomy and representation through the ADCs. Significantly, eight houses belonging to the candidates contesting in the ADC elections were attacked at Ukhrul Headquarters on May 31, 2010, just days before the scheduled June 2, 2010 ADC elections to intimidate people and force them to stay away from the election process. Significantly, most of the candidates whose houses were attacked belonged to the Tangkhul tribe that dominates Ukhrul and which supposedly supports the NSCN (IM)’s Nagalim project.

- The Ibobi Singh led Manipur state government has its own vested political agenda as well in this crisis, namely, using the ADC elections to negate the Naga unification demand. Hence, both parties are playing their own political games with the common man caught in between. Consequently, in this Naga-Meitei divide, the voices of tribes like the Kukis, who are supportive of the ADC elections, are being lost.

Second, when the ongoing crisis over the ADC elections was on, Thuingaleng Muivah, the General Secretary of the NSCN (IM) announced on May 4, 2010 that he intended to visit his native village, Somdal in Ukhrul district. This move was indeed motivated to earn political mileage from the ADC issue as well as visibly demonstrate his commitment to the Nagalim project to Nagas in Ukhrul at a time when many Tangkhul Nagas have started to express scepticism about the NSCN (IM)’s extortions and heavy handed ways. Subsequently, on being denied entry into Manipur by the Manipur state government, the NSCN (IM) led by Muivah also joined the blockade from the first week of May.

Third, the Naga Students’ Federation, in its latest meeting in the last week of May decided to intensify the blockade of NH-39 as a reaction to the Ibobi Singh Government’s decision to disallow NSF activists from entering Oinam village in Senapati district. Also, the NSF demands the withdrawal of section 144 of CrPC which has been imposed on Naga inhabited areas of Manipur since May 3, 2010.

The consequences of this blockade are manifold.

First, it has rekindled ethnic hatred and divides between Nagas and Meiteis so much so that the President of the Naga civil society body, the Naga Hoho (Naga Apex Tribal Council), Keviletuo Kiewhuo stated on May 22, 2010 in Kohima that “we want the total separation of the people, that is the Nagas and the Meiteis. We have to live as different identities, we cannot co-exist anymore.” The convener of the Coordination Committee of Naga Civil Society, Neingulo Krome, and its member secretary, Rosemary Dzuvichu, similarly argued that “The Nagas are fully aware that after more than six decades of political struggle, our future are [sic] bound together not only with our neighbours but also with the world’s community in a global village. But if our aspiration to attain our rightful humanity is constantly denied, we would rather face the challenges with the worth of human person than to live with humiliation.”

Second, the divide has become intensely politicised with the NSCN (IM) General Secretary Muivah and Manipur Chief Minister Ibobi Singh stoking dangerous ethnic divides.

Third, Manipur is facing a humanitarian tragedy of sorts. One kilogram of rice now costs Rs. 30; a litre of petrol is priced between Rs. 150 and Rs. 200. Diesel is not available in gas stations and a LPG cylinder is priced between Rs. 1000 and Rs. 1500. The Public Distribution System (PDS) is closed. Worse still, the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences and Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences, two main hospitals in Manipur, have stopped functioning due to non-availability of medicines.

Despite all this, not much has been written in the national media in contrast to the intense media focus on the blockade of the Kashmir valley in August 2008 over the Amarnath land dispute. The Union government’s role in igniting the crisis must be noted as well. When Muivah made his request to visit his village amidst the ADC election crisis in Manipur, and Ibobi Singh agreed, the Centre should have known that this will ignite negative passions amongst the Meiteis, who fear the NSCN (IM)’s agenda of Greater Nagalim. Muivah visiting Manipur during the Naga protests against the ADCs only validates Meitei fears that these areas will one day become a part of Nagalim. The Chief Minister of Manipur also appears to have drawn political mileage out of it by refusing entry to Muivah despite appearing ambiguous when he was first approached on the issue by the Centre.

What can be done?

Four steps need to be immediately taken to defuse the ongoing crisis.

First, the Naga Baptist Church Council has come forward to work towards defusing the crisis in consultation with the Manipur Church. This is perhaps a viable way, given the influence Church leaders enjoy in Naga society.

Second, the Union and state governments should work together to lift the blockade of a national highway. Such acts should be declared unconstitutional and anyone responsible for it must be held accountable in a court of law and given due punishment for disruption of public life. This will deter future blockades.

Third, the NH-53, from Silchar in Assam via Jiribam (Manipur) for movement of goods into Manipur is not a realistic option as the terrain is difficult for heavy trucks to ply upon. Airlifting of basic commodities and medicines should therefore be the first option.

Fourth, a committee of inquiry should be constituted by the Union government, comprising both influential Meiteis and Nagas in order to find ways and means to resolve the crisis quickly.

While ethnic divides are a reality in pluralistic societies like India, they are not intractable. Divisions of this kind can be handled through a framework of pluralism and inclusive thinking. The first and most important thing to do is to condemn such exclusivist narratives, and work towards meaningful bridging of the divide. For this to happen, one needs to go beyond the local state structures, which feed on ethnic divides for narrow political gains. Societies on both sides have to be brought together. While the Naga Hoho is appreciated for its efforts at reconciliation between Naga tribes, its recent statements about the inevitability of the Meitei-Naga divide smacks of irresponsibility and must be fittingly refuted and condemned as it only makes life difficult for the common man living in these heterogeneous ethnic spaces. Finally, it is social cohesion and determination by local communities to bring about peace that can realistically tide over vested political interests and narrow destructive narratives that seem to be informing the present crisis between Manipur and Nagaland.