NPT@50: How India Framed its Decision to Reject the Treaty

Summary: Contrary to notions that its orthodoxy on disarmament drove India’s rejection of the NPT, archival documents show that the decision was a display of astute statecraft with idealist posturing used to masquerade pursuit of national interests.

Summary: Contrary to notions that its orthodoxy on disarmament drove India’s rejection of the NPT, archival documents show that the decision was a display of astute statecraft with idealist posturing used to masquerade pursuit of national interests.

The dominant Indian narrative has been to project the ‘discriminatory’ nature of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) as the reason for India’s perennial opposition and that the treaty, as drafted by the then superpowers, cannot facilitate disarmament and, instead, could only sustain a world of nuclear ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’. However, as some recent literature and analyses illustrate, there were many other dominant factors including the domestic clamour in favour of developing nuclear weapons as a response to the repeated nuclear tests by China since 1964 that had seemingly shaped India’s decision to reject the treaty at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 1968.1

This issue brief, however, does not build upon these explorations to address the ‘why’ question. Instead, it uses recently accessed archival documents to narrate ‘how’ India framed its NPT decision, by shedding light on the confabulations and considerations of the Indian Government to arrive at the final decision.

Background to Treaty Decision

Even when initial disarmament negotiations in the early years of the 1960s veered around issues like ‘non-spread’ and ‘non-dissemination’ of nuclear weapons, the Indian quest was largely for a comprehensive disarmament instrument that could also address issues like nuclear test-ban, ending production of fissile materials as well as delivery systems, reducing stockpiles and facilitating their total elimination.2 This was India’s key position at the Eighteen Nation Disarmament Committee (ENDC), which was convened in March 1962 to negotiate such an instrument.3 However, the Indian approach began to change on the eve of the impending Chinese nuclear test with India’s representative, V.C. Trivedi, appealing to the ENDC to “prevent this proliferation” by proceeding to a disarmament treaty with measures to “prohibit manufacture, acquisition, receipt or transference of these weapons” – probably the first time when ‘proliferation’ crept into the lexicon.4

Following the first Chinese nuclear test and a pro-bomb clamour within the country, the Indian delegation charted a new course at ENDC which included the call for nuclear powers to reduce and eliminate their arsenals, the need to safeguard the ‘security’ of non-weapon states, an equitable framework of safeguards that does not inhibit their right to access and develop peaceful nuclear energy resources, and tangible progress towards disarmament. When the United States (US) and the Soviet Union submitted individual drafts of a non-proliferation treaty in 1965, it was becoming evident that the nuclear powers wanted to impose constraints on the non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS) even while being disinclined to assume commitments on their arsenals or charting a disarmament roadmap. India, along with other members of the non-aligned group, hence pushed for a balanced and non-discriminatory instrument through the Eight-Nation Joint Memorandum, which listed five principles for the potential non-proliferation treaty.5 Through Resolution 2028 (XX) of November 19, 1965, the UNGA accepted these principles as the basis for the treaty’s negotiations though it was proven subsequently that no such consensus resolution had stopped the superpowers from drafting a fragile non-proliferation instrument.

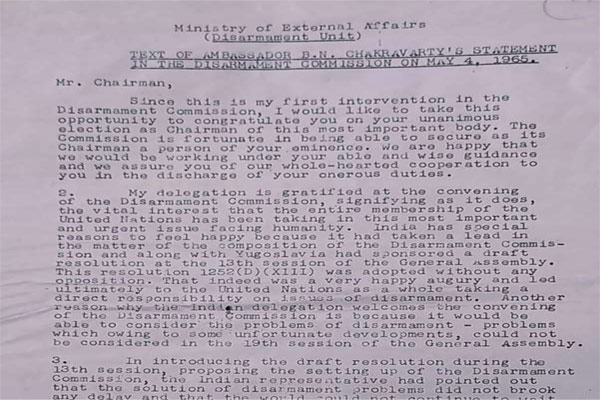

(B.N. Chakravarty’s Letter to UNGA)

The greater part of negotiations until the presentation of the US-Soviet joint draft in the ENDC was dominated by differences between the nuclear powers and the non-aligned group with the latter demanding measures to ensure obligations on the nuclear powers and facilitate a logical treaty that ‘stops all proliferation’ and be a credible means towards disarmament. Besides India’s lack of confidence on safeguards, two issues on which the Indian side had intense contestations were on the right to peaceful nuclear explosion (PNE) and the question of security guarantees. While India sought to link PNE as integral to the uninhibited access to all peaceful uses of nuclear energy, the US side, highlighting the perils of permitting nuclear explosive devices, proposed to provide PNE technology or services on a commercial basis to the NNWS. India vociferously dismissed such proposals terming them as ‘atomic apartheid’ and ‘atomic commercial super-monopoly’.6 On the other hand, despite demanding credible security guarantees to be enshrined in the treaty draft, India attempted a diplomatic mission, with L.K. Jha visiting major capitals to convince the nuclear powers,7 who, though, preferred providing guarantees to signatories of the treaty through the UN Security Council Resolution 255.8

Having driven a wedge among the NNWS by contending that tying up non-proliferation to other measures could delay the treaty, the superpowers managed to get the UNGA to adopt the draft treaty through Resolution 2373 (XXII) on June 12, 1968 with 95 votes in favour, four against, and the rest 21, including India, abstaining. India rejected the draft treaty by stating that it does not conform to Resolution 2028, that it did not have a balance of obligations to prevent all types of proliferation, that safeguards were not universally applicable and restrictions on PNE technology was one-sided, and that the treaty provides no time-limit to stop vertical proliferation or liquidation of arsenals while the undertaking on disarmament does not create any juridical obligation and is only an “imperfect obligation with no sanction behind it.” Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared in the Parliament that “we will now be driven by our self-enlightenment.”9

How India Framed its NPT Decision

Notwithstanding the passionate advocacy of disarmament and the crusade for third world rights, three documents prepared soon after the joint draft was presented at ENDC provide not just deeper insights on the discussions leading to the formal announcement of India’s NPT decision at the UNGA but also the thought process and strategic considerations that went into it. Two key features of India’s NPT decision are evident from these documents: (a) the decision to reject the NPT was made before the joint US-Soviet draft was tabled in ENDC (March 1968) and UNGA (April 1968), and (b) beyond the call of a third world crusader, the NPT decision was seemingly based on national interest, including keeping the nuclearisation option open, even while depicting a larger ‘idealist’ cause at work. The three documents are: (a) M.A. Husain’s detailed note on ‘NPT and Security Assurances’, (b) top-secret note titled ‘Non-Proliferation Treaty and Brief Answers’, and (c) Prime Minister’s Secretariat note with ‘Instructions to India’s Representative to U.N. on Non-Proliferation Treaty’.

(a) Advisory Note from M.A. Husain (April 11, 1968)

Husain’s detailed note of April 11 (along with treaty text placed in the ENDC on the same date) indicates that the decision to reject the treaty was taken well before the joint draft was being prepared by the US and Soviet delegations.10 Husain writes in the second section on ‘mode of presentation of objections’: “if Government’s decision not to sign the NPT continues to remain firm (emphasis added) despite the persuasion exercised by the USSR and USA, Canada and UK, urging us to reconsider our position, then, in the General Assembly views would need to be expressed similar to those made in the E.N.D.C.” Husain lists these views under ‘publicly stated objections to NPT’ as including: (a) it does not stop vertical proliferation; (b) does not establish a purposeful link between general and complete disarmament, in particular nuclear disarmament; (c) it would hamper peaceful uses of nuclear energy by non- weapon powers; and (d) it imposes inspection and control over non-weapon powers.11

Husain opines that these views should be maintained and expressed through a six-pronged strategy: (1) “without canvassing support for our views or proposing any amendments to the draft treaty so as to avoid any implication of committing ourselves to signing the treaty” – a clear indication that India did not want to sign the treaty, nor wanted to commit to any amendment (a potential improvement), or a disruption of the process through its activism. This strategy is further substantiated in the next line which says: (2) “without taking in any way a lead in opposing or obstructing the approval and conclusion of the treaty so as not to unnecessarily offend USSR/USA who are determined to the open the treaty for signature in July/August 1968” – which though also gives the impression that the ‘hands-off’ approach is to avoid offending the superpowers.

Husain then cautions about: (3) “avoiding acrimony, bitterness and polemical tone against the nuclear powers, so as not to provoke sharp rejoinders” – which has a significant symbolism of de-emphasising the third world cause. The need to take a subdued tone probably follows the acerbic debates over the drafts in ENDC, as well as the strong expression of sentiments on issues like PNE and security guarantees. It, hence, seems that the key negotiators were advising the need for a silent and inconspicuous exit from the whole process without drawing unwanted attention on its strategic schemes.

The same approach has been carried on for the next steps in this strategy. While step (4) recommends only a subtle reference to France boycotting the NPT process, to not prejudice any chance of future nuclear assistance, the reference to China also seeks similar caution. Husain suggests that (5) “while mentioning Chinese nuclear threat, India should not overplay it so as to avoid giving the impression that this was the principal reason for our not signing the NPT.” Husain underlines two significant reasons for underplaying the China factor: (a) the nuclear powers may attempt to address the China threat by providing more security assurances, and (b) it will add to greater domestic demand to change the national policy of not building the bomb. The first advice has far greater import in terms of challenging the notions about security guarantees, including the L.K. Jha mission. Departing from the assumptions that the nuclear powers were not forthcoming on security guarantees in the terms that India sought, Husain’s advisory indicates that India seemed keen to avert any such commitments from the superpowers, which could have curtailed its options on the NPT as well as potential nuclearisation.

Similarly, the advice about the domestic implications of the Chinese bomb could be seen as a judicious move intended to neutralise the pro-bomb lobby. Finally, Husain suggests the need to (6) “reiterate our policy of using nuclear energy only for peaceful purposes so as not escalate the arms race and to avoid jeopardising the national, social and economic programme of development” – which seems an indirect reference to the possibility of keeping open the channels of foreign aid for economic and technological domains.

Besides listing this strategy, Husain’s note goes on to deconstruct and highlight the perceived disconnect in some established positions that India took on the earlier drafts and proposals. Most significant is Husain’s assertion that India’s contentions about ‘vertical proliferation’ not being addressed by the NPT could remain untenable as most negotiating states saw the treaty as concerning the “prevention of wide dissemination of nuclear weapon,” and that another instrument might need to be formulated to address this aspect. This opinion, in fact, nearly uproots the foundational Indian positioning at the negotiating table, though Husain wisely suggests that the argument on ‘vertical proliferation has to be continued’ in order to “justify our decision not to sign NPT.”12

Husain also provides a different interpretation, contrasting the Indian sentimentalism surrounding the disarmament cause, by opining that it would be “difficult to justify the inclusion of nuclear disarmament measures in a treaty which concerns itself with only non-dissemination.” This opinion, however, may seem like a dissonance (and reflecting Husain’s pessimism) especially since the whole Indian campaign was about formulating a comprehensive disarmament instrument, and not a treaty that only addresses non-dissemination. Husain resorts to more contrarian opinions when he states that the Indian attempt to “make a distinction between the two types of explosives (peaceful and military) is scientifically untenable.” He also does not sound optimistic on the possibility of institutionalising PNE rights through an international body with the representation of NNWS.

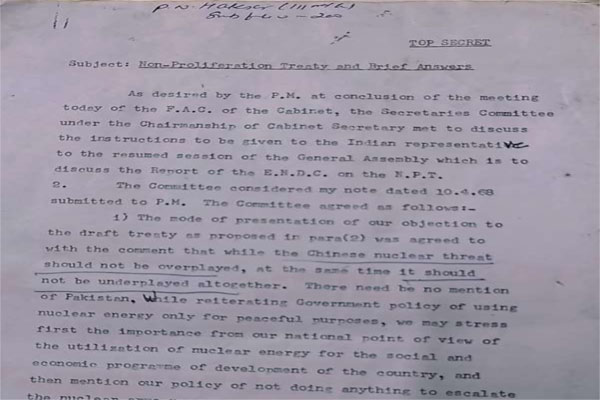

(Top Secret Note from M.A. Husain)

(b) Instructions from Secretaries Committee (April 18, 1968)

The Secretaries Committee, headed by the Cabinet Secretary, discussed Husain’s observations and decided on the instructions to be given to the Indian representative to the UNGA. The note prepared by this Committee, and circulated by Husain, agreed with his view that the Chinese threat should neither be overplayed nor underplayed and that no mention of Pakistan should be made.13 The Committee suggested that the government policy of using nuclear energy only for peaceful purposes be reiterated even while highlighting opposition to vertical proliferation ‘as in the past’, thus rejecting Husain’s contention. Similarly, the Committee suggests that the delegation should vote in favour of proposals to improve disarmament provisions, but by “safeguarding our decision not to sign the treaty saying the proposal do not go far enough to meet our viewpoint.” This is a remarkable position that embodies political tact to sustain the ‘idealist’ position with a pre-decided plan to reject any improvements as falling short.

The Committee also dismisses Husain’s views on PNE and instead decides to favour a separate treaty that will provide for the conduct of PNEs under international safeguards. Similarly, while retaining the position that safeguards should be uniformly applicable, the Committee suggests that “we need not lay stress to the extent of embarrassing USSR.” It is thus evident that the Committee does not expect any modification on the PNE provisions to happen, though it is hopeful of pushing for further rights on peaceful uses of nuclear energy (with Vikram Sarabhai, then chief of the Department of Atomic Energy, being asked to examine that area for any improved proposals). The Committee’s deliberations, along with Husain’s advisory, manifestly point to the fact that the Indian Government saw the NPT as a major challenge to its national interests and was determined to reject the treaty despite any improvements the nuclear powers could have proposed.

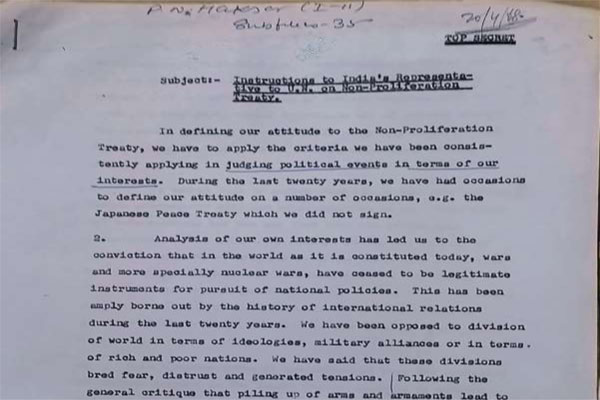

(c) Haksar’s Note with Instructions to Representative (April 20, 1968)

This sentiment is amply sounded in the opening paragraph of the covering note prepared by P.N. Haksar, Secretary to the Prime Minister, on ‘Instructions to India’s Representative to the UN on NPT’: “In defining our attitude to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, we have to apply the criteria we have been consistently applying in judging political events in terms of our interests.”14 The treaty, undoubtedly, impinged Indian interests in numerous ways: as a recognised nuclear-weapon state (NWS) and non-signatory, the treaty allowed China to build and expand its arsenal; having missed the January 1967 cut-off, India is denied the right to defend itself by exercising a nuclear weapon option if joining as an NNWS; the right to PNE has been curtailed; and security guarantees were not seen as credible enough and were linked to NPT membership.15 The ‘Instructions to India’s Representative’ profoundly echoes these concerns when it talks about keeping its options open and having the right to possess nuclear weapons, even when reiterating the intention of maintaining a peaceful programme.

(Instructions to India’s Representative to U.N. on Non-Proliferation Treaty)

Contrasting Husain’s observations, Haksar’s covering note highlights (probably to emphasise) the original contentions that were propagated to reject the draft treaty: that the treaty does not prevent vertical proliferation, that it could hamper legitimate use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes by non-nuclear states, that it would impose inspection and control only on these states, and so on. Further, the note suggests a stringent note on China, though not underlining its weapons programme, by highlighting its international behaviour instead and emphasising the fact that China not being a signatory to the treaty is a concern for India, especially with its hostile intentions, refusal to adhere to accepted international norms, and its ideology of interfering in affairs of other countries.

The note instructs the positioning to be taken by the Indian representative while participating in the UNGA discussions, which included avoiding a polemical tone against nuclear powers, reiterating peaceful programmes and utilisation for economic and social development, and commitment to refrain from the nuclear arms race, among others, as reflected in Husain’s note. It endorses the suggestion by the Secretaries Committee on voting in favour of new disarmament proposals, but not treating them as enough to accept the treaty. It instructs the representative to seek advice if a separate treaty for PNEs is being mooted. The position on safeguards being biased had to be maintained, though instructions have to be sought if any improved provisions are presented. Finally, the note instructs that the Indian delegation should emphasise the need for assurance for all non-nuclear weapon states and “express our objections to linking up such assurances with the NPT.” Nonetheless, the delegation is instructed to avoid proposing any specific amendments to the draft resolution, to abstain on the resolution as a whole and that “we should not spearhead any move for delay and postponement” – thus indicating the plan to allow the treaty to come into force without overtly challenging it.

Conclusion

It is obvious from the abovementioned set of instructions that the Indian Government wanted to toe a fine balance between diplomatic prudence and strategic caution (or brilliance). The instruction to maintain the established idealist positions without blocking the treaty’s passage, nor engage in disruptive polemics that might hamper this process or affect relations with the superpowers comes out as a historic example of astute statecraft practised by the then politico-bureaucratic leadership. The natural outcome of such consequential strategy being to abstain on the resolution, these insights come out as a significant counter-narrative to the historical portrayal of a country fighting for third world rights and eventually succumbing to great power politics before deciding to stay out of a ‘discriminatory and imbalanced’ treaty. That India decided to abstain and not vote against the resolution also embodied a willingness to accept the treaty in its presented form, and use it as a rationale to stay out and pursue its own ‘enlightened self-interest’. The glaring contrast seen from the public posturing of India’s campaign with clear identification and pursuit of national interests and strategic necessities makes this episode of decision-making a noteworthy chapter in independent India’s strategic history.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Some recent literature, including of the author, had attempted to explain the factors that influenced India’s NPT decision. See A. Vinod Kumar, “Between idealism, activism, and the bomb: why did India reject the NPT?” in Popp Roland, et.al, (eds.), Negotiating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Origins of the Nuclear Order, Routledge, London, 2016.

- 2. The momentum started with Ireland’s drafts for resolutions on ‘non-dissemination’ and for measures against ‘relinquishing control or transferring information on nuclear weapons manufacturing’ at the UNGA in 1960 and 1961. The eventual UNGA resolutions were 1664 (Question of Disarmament) and 1665 (Prevention of Wider Dissemination of Nuclear Weapons). Meanwhile, the superpowers had agreed on the US-Soviet Joint Statement on Agreed Principles for Disarmament Negotiations of September 1961, though both sides had not made any strides towards what could be a common draft of a disarmament treaty.

- 3. After the Soviets walked out of the Ten-Nation Disarmament Committee (TNDC) in June 1960, it was the US-Soviet framework agreement of September 1961 that enabled the establishment of ENDC with expanded membership for non-aligned participation. Despite ENDC being the forum that negotiated the NPT, it was not a UN body nor formed by a UNGA resolution though serviced by UN staff. For insights on this, see “Convening of 18-nation Geneva Committee on Disarmament – Credentials for Indian Delegation”, Note by K.S. Bajpai, Deputy Secretary to Joint Secretary (UN), 11-3-1962, File No. B (103)-DISARM-62, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

- 4. Indian representative V.C. Trivedi made his remarks at ENDC/PV.174, held on March 12, 1964. Also, in a letter to the UN Secretary General dated October 10, 1964 (six days before the first Chinese test), India’s representative, B.N. Chakravarthy, requested that an item entitled ‘Non-proliferation of nuclear weapons’ be inscribed in the agenda for the Nineteenth Session of the UNGA, thus formally introducing the concept.

- 5. The five principles were: the treaty should (a) be void of any loopholes which permit states to proliferate; (b) embody acceptable balance of mutual responsibilities and obligations; (c) be a step towards general and complete disarmament, particularly nuclear disarmament; (d) be acceptable and workable provisions to ensure its effectiveness; and (e) not adversely affect the right to conclude regional treaties to ensure total absence of nuclear weapons in respective territories.

- 6. India’s representative, M.A. Husain, made these descriptions at ENDC/PV.298 held on May 23, 1967 and ENDC/PV.370 held on February 27, 1968.

- 7. L.K Jha as Secretary to the Prime Minister went in April 1967 on a nuclear guarantee mission to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the US and the United Kingdom (UK).

- 8. Text of UNSCR 255, June 19, 1968.

- 9. Lok Sabha Debate on Foreign Affairs, April 05, 1968. The Prime Minister also spoke extensively on the treaty in Rajya Sabha debate of November 1967.

- 10. “N.P.T. and Security Guarantees”, Note from M.A. Husain, April 11, 1968, P.N. Haksar Papers, IIIrd Instalment, Subject File No. 200, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML), New Delhi.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Ibid.

- 13. “Non-Proliferation Treaty and Brief Answers”, Top Secret Note from M.A. Husain, April 18, 1968, P.N. Haksar Papers, IIIrd Instalment, Subject File No. 200, NMML, New Delhi.

- 14. In the covering note, Haksar points out that he has consolidated the two papers presented by Husain, which he indicated that the Prime Minister had seen. Haksar had added some preambular paragraphs in order to provide “continuity in our approach to NPT consistent with our foreign policy attitudes.” If Prime Minister approves the draft, he adds, it will be sent to Cabinet Secretary for circulation to the Cabinet for discussion (and decision). “Instructions to India’s Representative to U.N. on Non-Proliferation Treaty”, Prime Minister’s Secretariat, April 20, 1968, P.N. Haksar Papers, IIIrd Instalment, Subject File No. 200, NMML, New Delhi.

- 15. With the treaty marking January 01, 1967 as the cut-off date to recognise nuclear weapon states, China, despite staying away from the negotiations and not signing the treaty had all the privileges of NWS.