To Ban, or Not to Ban Huawei

Well before 5G could make its first full-scale commercial deployment,1 it is caught in a global spat over alleged snooping charges which saw Chinese telecommunication equipment manufacturers being banned from the international markets. More than half a dozen countries have either got Huawei off their 5G trials or are revisiting the company’s role in their 5G roll-out plans. American prosecutors have pressed criminal charges against Huawei for bank fraud, theft of trade secrets and breach of American sanctions on Iran, and even arrested the company’s Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou2 in December 2018. In a pushback, Huawei filed a lawsuit earlier this month, challenging the US law that bans federal agencies from buying its products and services.

It is noteworthy that 5G has set global players such as Cisco, Samsung, Ericsson, Nokia and Huawei scrambling to secure their share of the pie. The GSM Association forecasts 5G connections to reach 1.1 billion, around 12 per cent of total mobile connections by 2025.3 The competition is not immune to politics and power play, especially when it is destined to be a money spinner and an enabler for a host of much-awaited next generation applications including self-driving cars and the Internet of Things.

Chinese telecom players however have had a troubled history. The US had blacklisted Huawei and ZTE Corporation way back in 2012,4 when the House Intelligence Committee concluded that they pose a national security threat on account of spying, stealing of intellectual property and potential ties to the Chinese Government.5 The House Intelligence Committee could not ascertain the corporate structure, history, ownership, operations, financial arrangements and the management of Huawei, and recommended that the Committee on Foreign Investment must block acquisitions, takeovers or mergers involving Huawei and ZTE and government systems. In particular, sensitive systems should not include Huawei or ZTE equipment including component parts. The National Defense Authorization Act – signed in August 2018 – forbids government agencies from procuring telecommunications equipment or services produced or provided by Huawei and ZTE Corporation.6

Apprehensions over State influence in Huawei’s operations and products also stem from its founder Ren Zhengfei’s close ties with the Chinese Government and his previous employment with the engineering corps of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and thereafter in a state owned enterprise. Ren is not an ordinary serviceman; he was invited to the 12th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 1982. Huawei is the face of China’s growing technology prowess that was initiated in 1978 under Deng Xiaoping. Founded almost a decade later in 1987 at Shenzhen coastal special economic zone, Huawei now supplies products and builds solutions for around 1500 telecom networks in 170 countries, which helps connect one third of the world’s population.7

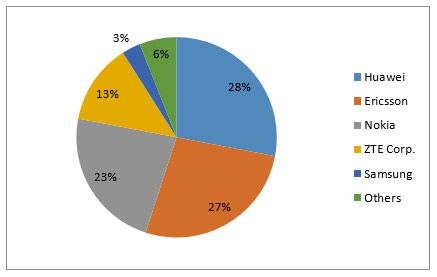

Over the last three decades, Huawei has carved out largest share in the global cellular base station market, pegged at 28 per cent8 (see Figure 1) with its telecom equipment revenue as large as Nokia and Ericsson put together.9 More than technology, cost effectiveness has helped Huawei a great deal; its equipment is said to be 20 to 30 per cent cheaper than the ones Nokia and Ericsson have to offer. Apparently, the US led allegations have not made any significant dent in Huawei’s revenue but has certainly kept Huawei on its toes all the while.

A Desperate Bid

As a fallout of the American ban, States both within and outside the “Five Eyes” (an intelligence alliance comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, US and UK) are revisiting their relationship with Huawei and ZTE Corporation. These entities, over the years, have made inroads not just in the telecom equipment manufacturing segment, but also in research and development,10 and a host of operations and business support services. In a bid to address the mounting concerns of the United Kingdom (UK) Government and intelligence agencies, Huawei had even set up a Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC) in 2010 – an independent security testing lab – entirely at its own cost. Huawei has left no stone unturned to assure Western governments and law makers that it is not a security threat. In 2011, it had published an open letter addressed to the US Government denying allegations levelled against it and reassuring that Huawei equipment is not a threat to its national security. The letter had clarified that it receives tax incentives from the Chinese Government, similar to the US companies, as support for some research and development initiatives.11

A similar letter addressed to Australian members of parliament (MPs) had surfaced in June last year12, amidst espionage concerns and possibilities of exclusion from the 5G roll-out from Australia. More recently, the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee asked Huawei for an explanation to both: the rising security concerns among members of “Five Eyes” alliance13 and the technical issues in its engineering processes raised in the report of HCSEC Oversight Board in July 2018.14 Again, in an open letter, Huawei refuted the concerns, and the reply was no different from its previous attempts to douse the fire. However, Huawei promised to invest US$ 2 billion over the next five years to improve its software engineering capabilities.15 Table 1 summarises the status of Huawei in the 5G roll-out across different countries, both within and outside “Five Eyes” alliance.

|

Country |

Impacted TSPs |

Status of Huawei on 5G |

|

US |

AT&T, T-Mobile US, Verizon |

Recommendations of the House intelligence committee in 2012 led to a ban on Huawei and ZTE Corporation on account of spying, stealing of intellectual property and potential ties to the Chinese Government.

National Defense Authorization Act of August 2018 forbids government agencies from using technology from Huawei and ZTE Corporation. |

|

Australia

|

Vodafone, Optus and TPG |

In 2012, Huawei was blocked from the bidding for the Australian National Broadband Network. One of the first responders, Australian Government blocked Huawei and ZTE from providing 5G technology equipment in August 2018.16 |

|

New Zealand |

Vodafone NZ, Spark |

New Zealand’s Government Communications Security Bureau blocked its top telecom firm from using Huawei equipment for its 5G mobile network in November 2018.17

However, there has been no final decision and New Zealand still has not ruled out Huawei from 5G network upgrade.18 |

|

UK

|

O2, Vodafone UK, BT |

In December 2018, British Telecom said it would remove Huawei’s equipment from its existing 3G/4G mobile operations.

UK maintains the stance that any risks posed by Huawei can be mitigated. |

|

Canada |

Telus, Bell Canada |

Canada is currently considering whether to Huawei from providing equipment for 5G cellular networks.19 |

|

Germany |

Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone, Telefónica |

Germany’s 5G spectrum auction began on March 20, 2019, and the government has not excluded Huawei from providing networking equipment.20

Germany has been vocal about its unwillingness to ban Huawei from building its 5G networks.21 |

|

France |

Orange, Iliad |

France does not plan to ban Huawei. Instead, it is stepping up controls and safeguards in telecom infrastructure for the next-generation networks in the form of a new amendment to draft business legislation.22

Orange has confirmed it will not be using Huawei as a 5G kit supplier in France. |

|

Japan |

NTT DoCoMo, KDDI, Rakuten |

In December 2018, Japanese Government banned Huawei and ZTE Corporation from official contracts for its upcoming 5G infrastructure. The top three telecom operators followed suit.23 |

|

India |

Airtel, Vodafone Idea Ltd. |

Huawei had received an invitation from the government in September to conduct 5G trials in India, along with Ericsson, Nokia, Samsung and Cisco.24

There is ambiguity as in late February the Telecom Secretary said that the government is yet to take a decision on whether to allow Chinese equipment makers or not. |

A Power Play?

The global response to Huawei’s role in 5G implementation has been mixed. The US is both persuading and pressurising its allies and members of the “Five Eyes” to do away with Huawei from their 5G deployment plans. During the 2019 Munich Security Conference, US Vice President Mike Pence called on security partners of the US to reject Huawei and other Chinese telecom companies.25 Within the “Five-Eyes”, Australia was quickest to follow suit. Germany and UK on the other end do not seem to be caving in to the American pressure, although the US has threatened to restrict intelligence sharing with allies who do not comply with its call for a ban on products and services from Chinese telecom majors. Meanwhile, China’s Ambassador to Canada has warned Ottawa of “repercussions” if it drops Huawei from its 5G plans. Both Canada and New Zealand, caught in a tug of war between China (economic reasons) and US (security reasons), are playing their cards cautiously and buying time before taking the final call.

From business point of view, the US does not have much to lose as 90 per cent of its wireless infrastructure rests on equipment from Ericsson and Nokia.26 For over six-seven years US has kept Huawei and ZTE Corporation at bay, although they are much more integrated to the telecommunications infrastructure among other countries listed in Figure 1, especially Huawei. Out casting Huawei and ZTE Corporation from the international market will have consequences both for the developed and developing economies. A retrospective ban means telecom service providers would need to spend a fortune in retro-fitting network gear. Already skewed profit margins mean that telecom service providers will quite likely pass on the cost to the customers. Taking a major player down can also shoot the prices up for 5G deployment, which is not a favourable case for developing economies.

If the US dogma is fuelled by technology competition, then this certainly is not the right way to quell the competitors. If it is about technology protectionism, then it may seriously undermine global technology research, innovation ecosystem and supply chains. And, if it is about power politics, then middle powers and growing economies are going to pay the price. Germany and UK stand out in this brawl, with a relatively mature and thoughtful approach. A threat to the US does not necessarily equate to a threat to other countries. There is no apparent reason for India either to blindly ban Huawei from its own 5G roll-out plans. However, the final decision should be based on an independent review of Huawei’s telecommunications equipment and the respective security situation. As the negative sentiment against Huawei grows, India can perhaps leverage the opportunity to bargain a better price from the global players for the roll-out of its 5G services. It could also be used as a bargaining chip to correct the trade imbalance vis-à-vis China.

India however would need to tighten few lose ends at the security front domestically and walk a tight rope at the political front internationally. The Indian Telegraph (Amendment) Rules 2017 provision mandatory testing and certification for telecom equipment prior to sale or import in India, under the Mandatory Testing and Certification of Telecom Equipment (MTCTE) rules of the Telecom Engineering Centre (TEC).27 Performance testing encompasses safety of the equipment with radio interface, its immunity to electrostatic discharge, operating frequency, output power and conformance to receiver and transmitter parameters.28 The deadline for enforcement of MTCTE procedure has already been pushed from April 01 to August 01, 2019.29 Moreover, there is acute ambiguity over the status, functioning, capacity and competence of Security Lab under the TEC30, whose role is critical in the aftermath of snooping allegations on Chinese equipment manufacturers. Security lab of such significance and scope should possess the competence to rip apart a telecom gear and review the components at both source-code and hardware levels.

India’s decision to allow Huawei to bid for India’s 5G infrastructure development and continue its investments in manufacturing and R&D should be in line with its own national interest, rather than taking sides and constraining options. For India, whose 90 per cent of telecom equipment (worth US$ 21,847.92 million31) is imported,32 the concerns over foreign surveillance would always loom large, whether it is Huawei (China), Nokia (Finland) or Ericsson (Sweden). Since domestic production is a bridge too far, it is the ability to test and verify security aspects of the imported equipment that can mitigate the risks and instil confidence in the near term.

Views expressed are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “ITU’s Approach to 5G”, ITU News, October 15, 2018 (accessed March 08, 2019).

- 2. Meng Wanzhou is the daughter of the company’s founder Ren Zhengfei. She is facing extradition proceedings in Canada where she was arrested in December at the request of the US.

- 3. “New GSMA Report Highlights How 5G, Artificial Intelligence and IoT Will Transform the Americas”, GSMA, September 12, 2018 (accessed March 15, 2019).

- 4. The ban also covers video surveillance and telecommunications hardware produced by China’s Hytera Communications, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Company and Dahua Technology Company. See Catherine Shu, “New defense bill bans the U.S. government from using Huawei and ZTE Tech”, TechCrunch, August 13, 2018 (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 5. Mike Rogers and Dutch Ruppersberger, “Investigative Report on the U.S. National Security Issues Posed by Chinese Telecommunications Companies Huawei and ZTE”, U.S. House of Representatives – 112th Congress, October 08, 2012.

- 6. “H.R.2810 – National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018”, U.S. Government Publishing Office, December 12, 2017 (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 7. “Corporate Introduction”, Huawei (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 8. Isao Horikoshi, Takashi Kawakami and Kosei Fukao, “Huawei blacklisting bites 5G carriers in the wallet”, Nikki Asian Review, February 05, 2019 (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 9. “Key Takeaways – The Telecom Equipment Market 3Q 2018”, Dell’Oro Group, December 07, 2018 (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 10. “Huawei UK Research Centre”, Cambridge Science Park (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 11. Robert Olsen, “Huawei’s Open Letter To U.S. Investigators”, Forbes, February 24, 2011 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 12. “Huawei is good & safe for Australia: A Letter to Australian MPs”, Huawei (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 13. “Security of the UK’s Communications Infrastructure”, Letter of Chair of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee to Huawei, UK House of Commons, January 15, 2019.

- 14. “Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC) Oversight Board Annual Report 2018”, July 2018.

- 15. “Re: Security of the UK’s Communications Infrastructure”, Letter to Chair of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, Huawei, January 29, 2019 (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 16. “Government Provides 5G Security Guidance To Australian Carriers”, Ministers for Communications and the Arts, August 23, 2018 (accessed March 18, 2019). Also, see Arjun Kharpal, “Huawei and ZTE banned from selling 5G equipment to Australia”, CNBC, August 23, 2018 (accessed March 18, 2019).

- 17. Sherisse Pham, “New Zealand prevents mobile carrier from buying Huawei 5G tech over security fears”, CNN Business, November 28, 2018 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 18. “Huawei never excluded from New Zealand’s 5G network construction: NZ PM”, Xinhua, February 20, 2019 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 19. “Huawei likely faces 5G ban in Canada, security experts say – but the trick will be how and when to announce it”, South China Morning Post, February 07, 2019 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 20. Arjun Kharpal, “US allies defy Trump administration’s plea to ban Huawei from 5G networks”, CNBC, March 21, 2019 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 21. “Germany does not want to ban Huawei from 5G networks: minister”, Reuters, March 08, 2019 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 22. “France tightens 5G network controls amid Huawei backlash”, Reuters, January 25, 2019 (accessed March 20, 2019).

- 23. “Japan to ban Huawei, ZTE from govt contracts –Yomiuri”, Reuters, December 07, 2018 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 24. “Making India 5G Ready – Report of the 5G High Level Forum”, Prepared by the 5G Steering Committee, Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Telecommunications, Government of India, August 23, 2018.

- 25. “Remarks by Vice President Pence at the 2019 Munich Security Conference”, The White House, February 16, 2019 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 26. Henry B. Wolfe, “Australia Should Reverse Its Huawei 5G Ban”, Paid for and Posted by Huawei, The New York Times (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 27. “About MTCTE (Mandatory Testing & Certification Of Telecommunication Equipment)”, Telecommunication Engineering Centre, Government of India (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 28. “Base Station for Cellular Network”, ER No.: TEC4272418, Telecommunication Engineering Centre, Government of India, 2018.

- 29. “Notification: Mandatory Certification of Telecom Equipment”, No. TEC/1-/2018-TC, Telecommunication Engineering Centre, Government of India, March 12, 2019.

- 30. Scope is mentioned as “testing the security features of all types of IP and telecom / ICT equipments in access, transport, control and application layers of wireless and wireline domain deployed in the telecom network e.g. NGN, IMS, LTE etc.” See “Scope of Telecom Security Test Lab”, Telecommunication Engineering Centre, Government of India (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 31. “TRAI calls for zero telecom equipment imports by 2022”, The Hindu, August 03, 2018 (accessed March 11, 2019).

- 32. Mehul Pandya, “Indian Telecom Equipment Industry – Will 5G Drive The Future Growth?”, Communications Today, December 2018 (accessed March 11, 2019).